“Nobody could tell me, when I began reporting in Rwanda a year after the genocide, how a nation that had been so diabolically hacked apart could ever be put back together. Nobody spoke of peace except as a bitter illusion.”

“Rwanda, for all its Edenic natural splendor, was a wasteland. Death and flight had emptied the country of close to 40 percent of its population, and as many as half of those who remained were displaced from their homes. Hutu Power, in its rout, had systematically reduced the country’s physical, economic, social, and administrative infrastructure to wreckage. Hospitals, banks, schools, farms, courts, markets, churches, municipal halls and national ministries, public utilities and private enterprises—nearly everything was stripped and broken. A team from the World Bank had just pronounced Rwanda the poorest country on earth. A government spokesman told me that some of the World Bank team had gone further, declaring Rwanda “nonviable.”

The prisons were the first public institutions to start running again at full capacity, and by the time I arrived they, too, had already proven inadequate, as they were packed wall to wall with nearly a hundred thousand men, as well as thousands of women and children, all accused of genocide. When international observers protested the hellish conditions, they were urged, ominously, to consider the alternatives. Rwanda’s violence was far from spent. Every day, from all quarters, there were reports of killings. Every day was an existential political crisis. Every day there were rumors of war. “Ça va eclater”—“It’s going to blow up”—was the refrain.”

— Philip Gourevitch, The Burden of Memory and Forgetting

In Rwanda, they collaborate with the regional monarch (Mwami).

The Belgians lead a successful campaign against the Germans and capture Rwanda.

While traditionally the two ethnic groups, Hutu and Tutsi, shared some fluidity of power and identity, the Belgians institutionalize Tutsi rule.

Under the new classification of “Trust Territory”, the Belgians must prepare Rwanda for self-rule.

In regional newspapers, Hutu elites argue with ruling Tutsis about historical injustices.

The Belgians reduce King Rudahigwa’s governing role, only to anger the Tutsis.

King Rudahigwa dies, and his successor, King Kigeli V, fails to hold onto power as Hutu purges begin forcing Tutsis to flee. Both sides take life in the struggle for control.

Kayibanda rises to the the top, with his more radical and Catholic aligned PARMEHUTU party winning the legistlature.

Kayibanda’s forces best them decisively, and follow up with Tutsi purges and massacres, estimated as high as 10,000.

Habyarimana outlaws all political parties other than his own.

They begin to plan an eventual Tutsi invasion of Rwanda. They join the Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF) and rise quickly through it’s ranks.

Lead by Rwigyema, they finalize the plans for invasion.

Rwigyema is killed, and the initially successful assault is beaten back by Habyarimana’s forces bolstered by French and Belgian aid. Paul Kagame, studying at Westpoint in the United States, rushes back to take over the RPF forces.

The leaner RPF manages to hold territory in the North of the country. Paramilitary massacres of Tutsis resume, encouraged by propagandist Radio Rwanda.

Hutu hardliners begins to build organizational infrastructure for genocide separate from Habyarimana’s influence.

As the RPF and Habyarimana settle into a ceasefire and agree on a power sharing agreement, Hutu hardliners cut out of the negotiations react with a spree of attacks on Tutsi civillians.

RPF killing of Hutu civilians alienates it from potential moderate Hutu allies. Over one million Hutu flee their homes to refugee camps both within and outside the landlocked nation.

The RPF and Habyarimana agree to a demilitarized zone between northern RPF territory and the capitol Kigali. The accords call for a UN peacekeeping force, UNAMIR.

The assassination serves as a propaganda boon for Hutu Power.

In the now-infamous “Genocide Fax”, Dallaire informs the UN of these revelations, only to be denied the authority to raid the arms caches.

Hutu Power and the RPF are both accused of the assassination. Hutu Power, lead by army Col. Theoneste Bagosora, purges moderates that very night and seizes control of the government.

Dydine Umunyana, three and a half years old when she witnessed the Rwandan genocide, is the author of Embracing Survival. Her memories of narrowly surviving the genocide remain as fresh as the milk she carried on one fateful day, but the fright did not end there. While the killing stopped, the violence didn’t—she spent much of her childhood avoiding the anger of her traumatized father. Umunyana is now a motivational speaker, committed to establishing a dialogue between people for understanding their shared histories and cultural differences.

On the morning of Thursday, April 7, 1994, I walked, still half-asleep, into the living room of my grandparents’ house. I was yawning and desperately wanted to go back to bed, but my Auntie Agnes was waking everyone up. My older cousins sat together on the mat in the living room.

Something strange was happening. I looked to see if it was morning, but the lantern on the table was lit and no light came through the windows. Auntie Agnes told us not to look outside, to sit quietly on the floor. She seemed to be the only adult in the house. I saw no sign of my grandparents. Auntie paced back and forth, wringing her hands. I had never seen her like this.

I lost my cousin’s hand. In a split second, I realized that I was alone, separated from my family. I was swept along with other people fleeing for safety. The next thing I knew, I was in the front yard of one of our Hutu neighbors. I looked down to find my beautiful white dress stained bright crimson with blood. I wasn’t little Dydine anymore. I looked around, but my family was nowhere to be found.

Only minutes after being separated from my family, I’m lined up with many other Tutsis in the front yard of one of the Hutu perpetrators, waiting to learn our fate. I’m still clutching the jar of milk I was drinking when my Auntie Agnes rushed my cousins and me out of the house. I look down and see dead bodies at my feet. In the distance, people wail as they are slaughtered. Whistles, blown by Hutus celebrating the massacre, echo across the hills.

My small body trembles. I am sweating. What have I done to be hunted this way? Something big is about to happen.”

— Dydine Umunyana, Butterflies Sat Next to My Heart

The rate of killing is five times higher than that of the Holocaust. The RPF estimates that 94% of those killed are Tutsi.

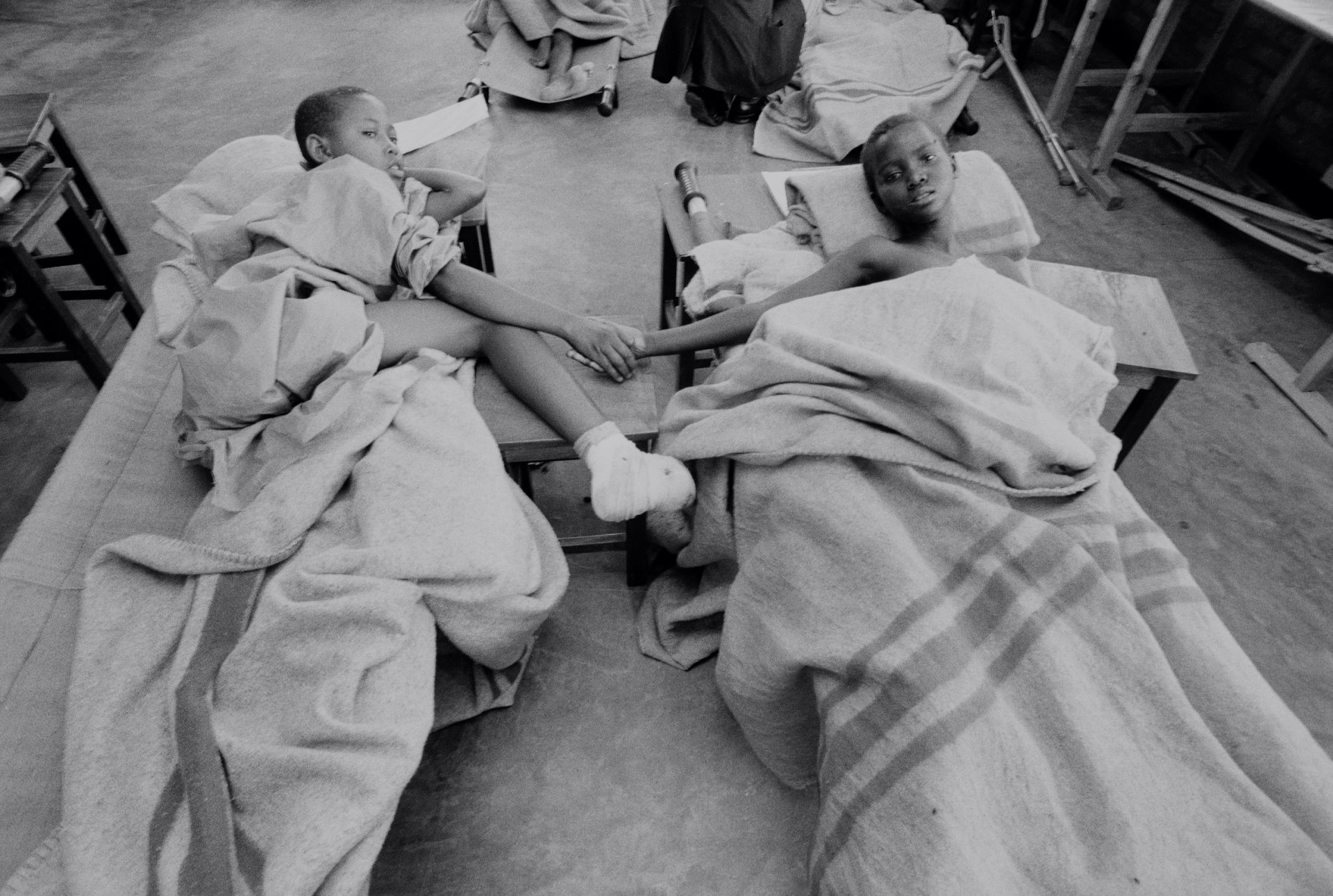

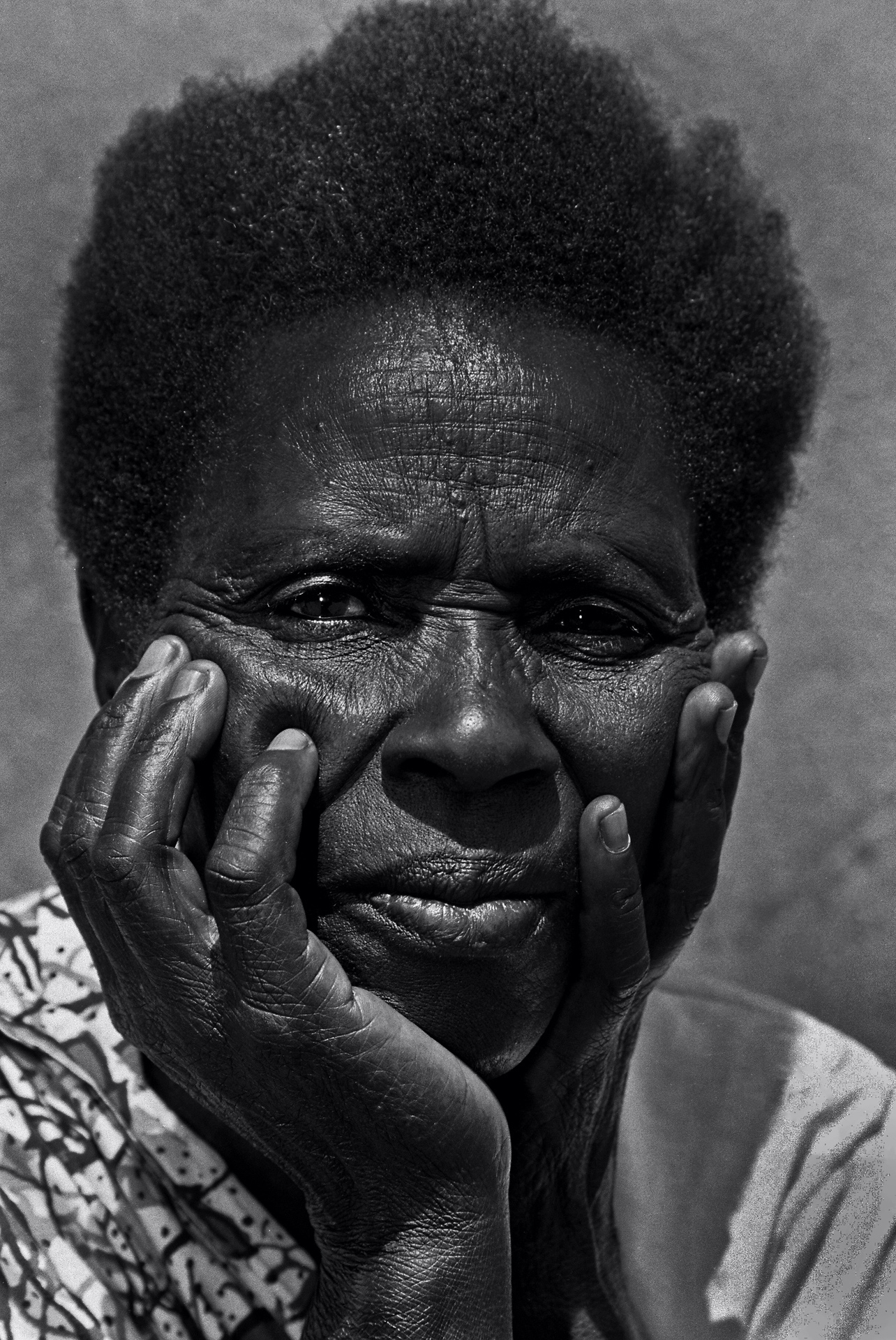

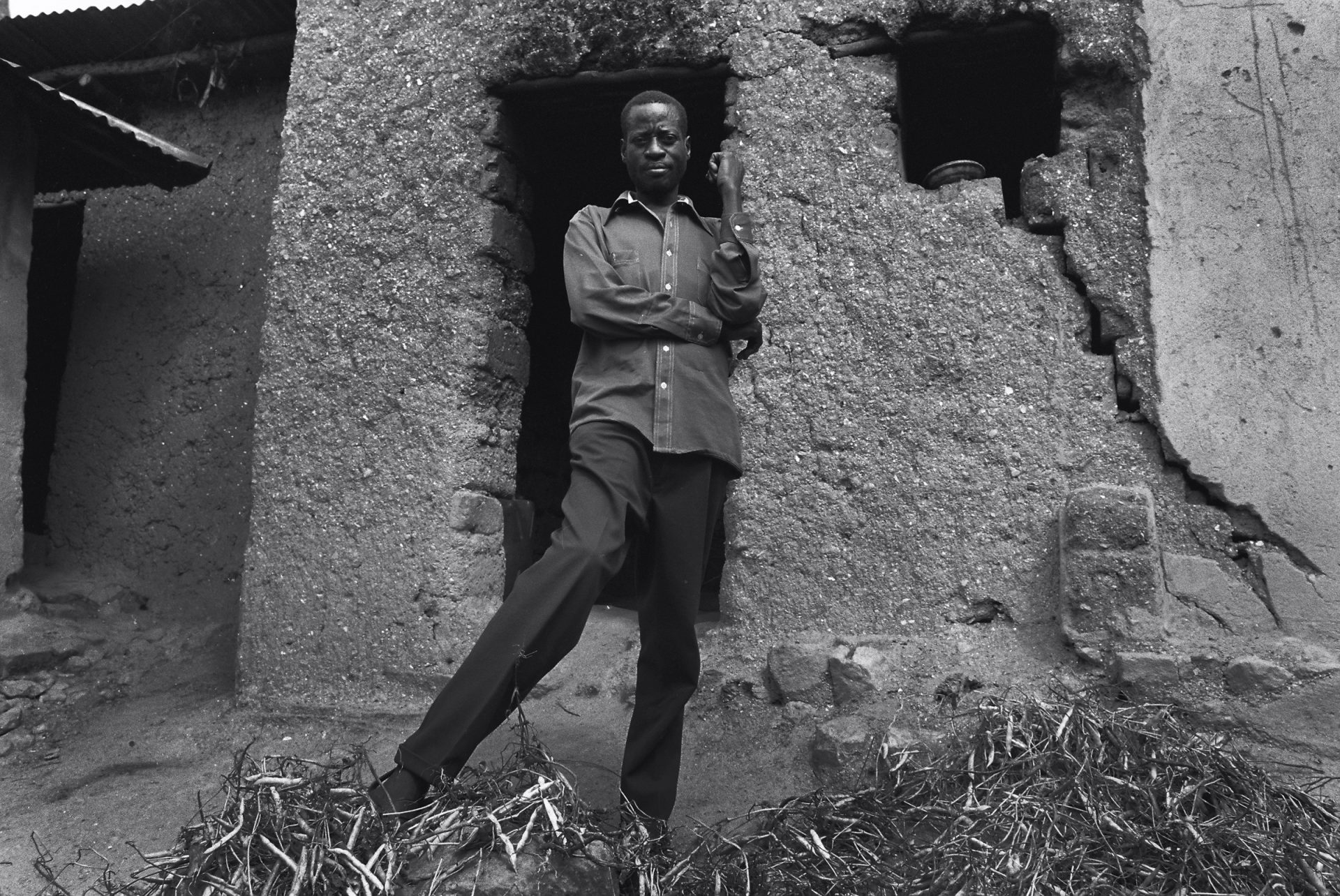

In 1994 as Rwanda was in the throes of genocide, I illegally crossed the Ugandan border to document one of recent history’s darkest events. I witnessed a broken country gouged, burnt, scarred and littered with corpses.

Twenty-five years later, I revisited Rwanda and found a very different country. A country that carries the genocide with it in its collective memory but refuses to be defined by it. A country once gouged is now full, a country once broken is now whole and scars once obvious are fading. Rwanda’s transformation is squarely rooted in the Rwandan people’s unparalleled ability to forgive.”

— Jack Picone

Jack Picone is an Australian documentary photographer, author and academic. He was one of only a handful of journalists to document the genocide in Rwanda. He returned to Rwanda in 2019 for this project.

Thousands die in the camps as disease spreads, and former genocidaires attempt to reorganize.

The First and Second Congo Wars bring multiple regime changes to what will become the DRC, as central African nations form alliances on both sides. Hutu Power and the RPF clash once again and thousands more are killed.

In 2000, the army finally put down the insurgency in the northwest, driving the Hutu Power forces back into Congo, and a decade after it began, the war in Rwanda could at last be said to be over. But there was no celebration. The damage was too great. The divisions were too deep and too raw. Everyone was in shock. The past was omnipresent. There was no other subject. There was nowhere to turn without slamming into it.”

— Philip Gourevitch, The Burden of Memory and Forgetting

Based on traditional forms of communal justice, the courts would work towards transitional justice centred on reconciliation.

She said, “One person cut me here”—she touched her forehead—“and my arm. Others clubbed me. My kid was killed. My niece was cut. Now she’s handicapped. My husband was thrown in the river. After the 29th the RPF came. God used them. God bless them. God bless the government of Rwanda. I was elected a judge of gacaca. Then this person who’d been in prison came to me. He asked me for forgiveness. It was hard for me and for my family to forgive him. Now we share life. And he comes to visit us.”

When Alice left the dais, a man took her place at the microphone and said his name was Emanuel. His voice was fainter than Alice’s, more distant, and he spoke more slowly, but no less deliberately: “I am a genocide convict. I come from Nyamata in the Bugesera region. On April 11 many soldiers came. They told me to come and I went with them. It was to kill people. We went to the home of a man named Utasa. I killed 14 people. Then we butchered cows. On the 12th I killed a doctor called Gikangwa. I was able to steal a case of Fanta. On the 13th I killed three women and one child. Then on the 29th we were loaded on buses to Ntarama. We were able to kill so many there…. In prison I confessed. So by the president’s order I was released. In my heart I wanted to ask forgiveness but I was afraid. This lady who is here, I cut her and left her for dead. How could I go to her? Gacaca made that easier. Now I stand before you guilty of horrible crimes. You, too, all of you here—I ask you for forgiveness.”

The motto of the gacaca courts was “Truth Heals.” But how could such recitations of annihilating brutality close the wounds they described?

— Philip Gourevitch, The Burden of Memory and Forgetting

Rwanda agrees to withdraw as the DRC agrees to disarm Hutu militias associated with the genocide.

The courts are criticized externally on legal merits, but begin to find domestic success according to the communities utilizing them

Philip Gourevitch is a longtime staff writer for The New Yorker. His book We Wish to Inform You That Tomorrow We Will Be Killed with Our Families: Stories from Rwanda is widely regarded as the definitive piece of reporting on the genocide that took place inside Rwanda over 100 days in the spring of 1994.

Gacaca constituted the most ambitious and comprehensive exercise in accountability for crimes against humanity that any country has ever undertaken. In the course of 10 years, 160,000 citizen judges, in more than 12,000 jurisdictions, decided more than 600,000 cases relating to violent genocide crimes—killing, rape, and torture. Twenty-one percent of these were resolved by confession, 44 percent resulted in a conviction at trial, and 35 percent ended in acquittal. (By way of contrast, Rwandan officials liked to note that the UN’s International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda, which sat in Arusha, Tanzania, for 17 years, had convicted 61 individuals and acquitted 14, at a cost of about a billion dollars, which was roughly 20 times more than Rwanda spent on the entire gacaca system.)”

— Philip Gourevitch, The Burden of Memory and Forgetting

The investigation and subsequent warrants fray diplomatic ties with the Kagame-lead Rwandan government, which begins in turn accusing the French of assisting in the genocide.

Infrastructural improvements and expansion of agricultural exports and tourism continue to strengthen the small nations economy. The country is told to put the past behind them in the effort to rebuild. For many the trauma is never very far away.

There is no life after this mass killing,” my dad would say, sounding like a very old man. “When I close my eyes at night, I dream the Interahamwe are here. I see them raise their machetes to kill my children. My only comfort is the thought that I can take my gun and kill us quickly, before they hack us to death.”

I was always puzzled by my father’s dark dreams. Why did he want us to die when we all had fought so hard to live?

After one too many bad nights, my mother left my father, taking us children with her. We moved to new houses constantly so that he wouldn’t find us.

I was in a deep sleep one night when an arm came through the window, trying to grab me. I heard a voice whispering my name and asking for help. I screamed so loudly that my mother woke and ran into my room. She shrieked when she saw my father trying to squeeze through the bedroom window. She corralled all the kids into her room. How had he found us?

Dad’s voice called out, “Dydine, my darling, open up for me—you know I love you so much. Don’t be like your mother. It’s so cold outside.” These were the first tender words I’d heard from an adult in so long. I started crying and trying to pull away from my mother to open the door. Mom wrenched me back so forcefully that I thought my arm would tear from its socket. Dad began gathering stones and throwing them through the windows. He smashed every window in the house. Terrified cries rose from the houses of our neighbors. No one knew this madman in the night.”

— Dydine Umunyana, Butterflies Sat Next to My Heart

The wars in Congo are largely seen as, at least in part, aftermath from the Rwandan genocide and subsequent Hutu exodus, though Rwanda’s involvement in the conflict has waned since 2002.

Cases can range from torture and murder to property offenses. A Human Rights Watch report details a mixed legacy of providing an infrastructure for reconciliation, notwithstanding some significant oversights in its mandate and legal process.

The court fails to prove to a legal standard, in any case, that the genocide was planned prior to the Habryarimana’s assassination.

Radio Stories. Radio was a persuasive form of communication during the genocide, using hate speech to encourage citizens to rise up and murder hundreds of thousands of their compatriots. In the same way that the radio had encouraged violence, post genocide, a Dutch NGO saw the possibility of using it to debunk prejudices and encourage reconciliation. Radio La Benevolencija launched the radio soap opera Musekeweya or “New Dawn” in 2004. The weekly episodes continue to discuss issues of trauma and distrust through their soap opera characters and inspire dialogue and conversation.

VIIF Films with thanks to the Global Reporting Centre

Video is password protected, for access please contact:

[email protected]

Rwandan gorillas. The mountain gorilla population is the only great ape species on the increase and is encouraging the growth of eco-tourism benefiting both the national economy and the endangered species.

VIIF Films with thanks to the Global Reporting Centre

Video is password protected, for access please contact:

[email protected]

The president is charged as authoritarian while opposition politicians disappear or are found dead

Kagame responds by opening an investigation into French officials suspected of involvement in the genocide.

Countries that have recently been at war are more likely to backslide. Parliamentary representation and female literacy are particularly significant when it comes to reducing the risk of relapse into war: a study found that when 35 percent of parliamentarians were women, the risk of relapse was near zero (“Female Participation and Civil War Relapse,” Civil Wars, 2014). Rwanda is an instructive case. During the 1980s and early 1990s, women were 58 percent as likely as men to be literate, while they held just 13 percent of parliamentary seats. In the decade following the 1994 genocide, women became 85 percent as likely as men to be literate, and they made up 21 percent of parliament on average. Women’s representation now stands at 61 percent—the world’s highest percentage of women in parliament. Rwanda’s peace has held.”

— Marie O’Reilly, The Essential Presence of Women in Peace: The Liberian Example

Twenty-five years after the genocide, this marks the nation’s largest growth year since 2008.