Research shows that where women have access to power, war is less likely to break out in the first place.”

— Marie O’Reilly, academic researcher

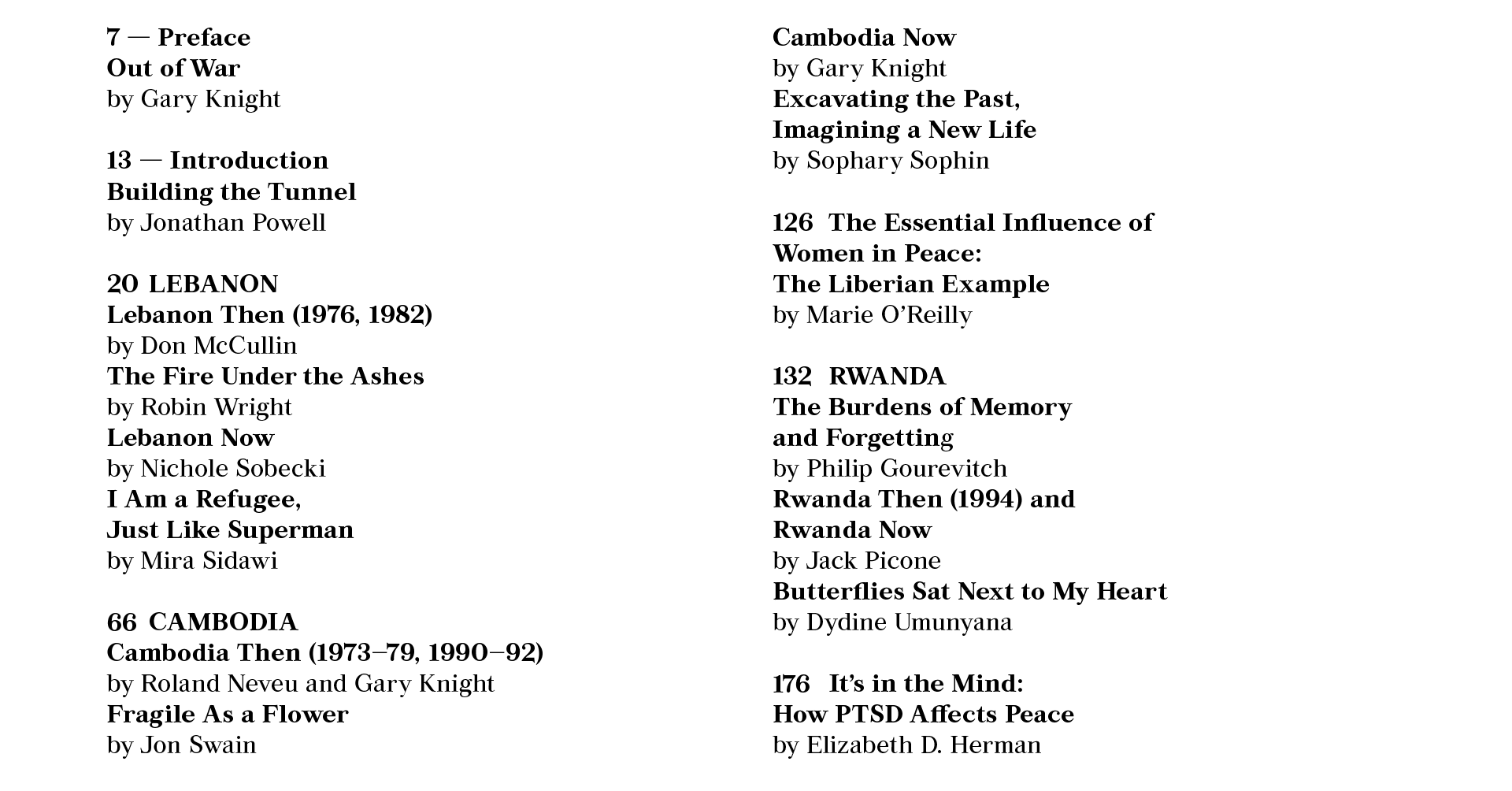

Women’s influence on peacemaking tends to get overlooked when men in suits broker deals with men in fatigues. According to a study by UN Women, 96 percent of those who sign peace treaties are men. Since 1901, a mere 13 percent of Nobel Peace Prize laureates have been women.

Yet research shows that where women have access to power, war is less likely to break out in the first place. Research into four decades of international crises by Mary Caprioli and Mark Boyer demonstrated that as the percentage of women in parliament increased by 5 percent, a country was five times less likely to use violence against another country (“Gender, Violence, and International Crisis,” Journal of Conflict Resolution, 2001). And Swedish scholar Erik Melander demonstrated that having a greater proportion of women in parliament also reduced the risks of civil war and domestic human rights abuses.

Moreover, evidence is mounting that women’s participation is essential if peace is to last. While warring parties traditionally focus on dividing power and territory in peace negotiations, when women get involved, they consistently emphasize the need for human security—prioritizing social and economic needs, as well as advocating for marginalized groups. This was the case in Liberia as well as Colombia and Northern Ireland. Frequently, these underlying grievances and inequalities drive conflict, so women’s participation, by addressing them, often helps to build a more robust peace.”

— Marie O’Reilly, academic researcher

The Essential Presence of Women in Peace: The Liberian Example

Monica McWilliams and Avila Kilmurray are activists and academics who fought for and won a seat at the peacemaking process in Northern Ireland. They conceived of the bilateral Northern Ireland Women’s Coalition, designed to force attention away from political posturing to the real social issues that affected both loyalists and nationalists.

The new system provided an opportunity for us, a group of community-based women, to get a seat at the table. We saw ourselves as accidental activists, since we had mostly been focusing on the small “p” politics—of poverty, childcare, and community development—rather than the big “P” politics of constitutional issues. Small “p” politics took the form of participation in community-based organising, setting up women’s centres, tackling domestic violence and sexual abuse, and meeting the needs of women on both sides of the “peace walls.” Big “P” politics took sides, formulating arguments rather than seeking out niches of commonality, dominating media headlines rather than working quietly. The peace talks provided us women with the chance to step out and be heard.

Starting with around 100 women, the NIWC grew. Local groups came together across Northern Ireland. Over 90 women agreed to stand for election in order to gather enough votes for the NIWC to be one of the 10 parties represented at the peace talks. We agreed to have two leaders: Monica McWilliams, from a Catholic and nationalist background, and Pearl Sagar, from a Protestant and loyalist one. We knew we had to structure the party to represent women from both sides of our divided community. We adopted a party platform of three principles—inclusion, equality, and human rights—rather than wasting time on drafting detailed policies. We did things differently: our election poster was a cartoon dinosaur in suffragette colours (green, white, and violet), declaring “Say Goodbye to Dinosaurs.” Some male politicians took offence at that.

Many of our positions were controversial. For example, we argued with sceptics and often-cynical government officials on behalf of victims of the conflict and political prisoners. We promoted integrated education for schoolchildren and shared housing for both communities. We looked at institutional reforms in the context of human rights and equality. Our ideas became an integral part of the Good Friday or Belfast Agreement of 1998, despite having been previously dismissed.”

— Monica McWilliams, Avila Kilmurray, The Hen Party

Now we have 36 colleagues, with one demining team and three bomb-disposal teams. The women in my team are very strong. But when I go to the small villages, the women don’t understand about themselves, about women’s rights or about what they can do. That’s why I try very hard to meet with the villagers, to motivate the young women. Some ask me, “What about your job?” I say I am (in) bomb disposal or demining. They say, “Women can do that?”

Right now we have women in political life and in government, but it’s not a big number. The balance is not there yet. It would be better if we women were more active. An easy example, a very simple example, is in the family: if wives and husbands both earned money, they could both support their children to go to school, and even if they are divorced, wives could send children to school. I believe a husband and wife can be happy together if they can be partners, share an idea, or together earn money to support the family. Then they may feel close and respect each other. That is a small case, but, you know, very simple, big effects.”

— Sophary Sophin, Cambodian bomb disposal engineer

A most important lesson to be learned from the history of the international criminal courts and tribunals is that victims of massive crimes cry out for, and indeed demand, some form of accountability and justice.”

— Justice Richard Goldstone, chief prosecutor ICTY, ICTR

If that call is thwarted, there will be a cancer in that society which, sooner or later, will manifest itself in further cycles of violence. The history of the Balkans and Rwanda provides evidence in support of this assertion. To that extent, at least, justice mechanisms have helped maintain peace in a number of postwar societies.

The work of the ICTR also allowed the Government of the Republic of Rwanda to turn to a form of traditional justice (gacaca) to investigate the guilt or innocence of tens of thousands of suspects who had been held in grossly inadequate prisons. Judged by modern international standards, gacaca was hardly a fair system of justice. However, it provided a solution to the intractable problem of bringing closure to the allegations made against the suspects. Today, there is no longer violence between the Hutu and Tutsi people of Rwanda. Whilst Rwanda is by no means a model democracy, peace and prosperity are manifest in the African nation.

Other forms of transitional justice are able to give victims their due and bring peace to nations. The most obvious is a truth-and-reconciliation commission. It was such a commission that made public many of the horrendous crimes committed by the apartheid government forces in South Africa. The truth-and-reconciliation process helped South Africa ameliorate the political animosity and divisions of the apartheid era. Those divisions have not, by any measure, disappeared—the inequities in post-apartheid society are still all too present in the unequal society that remains, more than two decades after South Africa became a democracy.”

— Justice Richard Goldstone

No Mere Postscript to War: The Role of International Criminal Courts

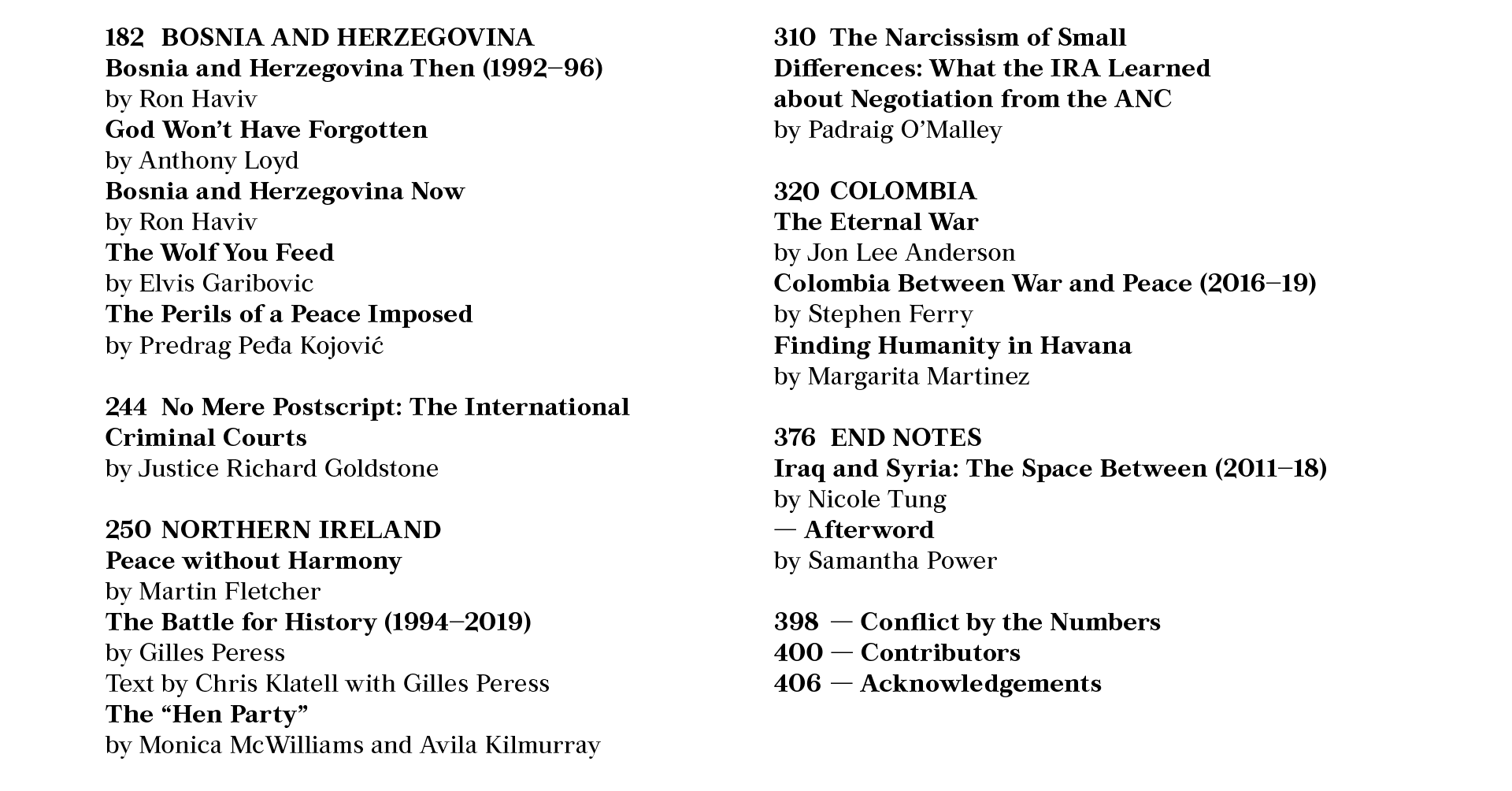

Chantal understood that the genocide had come from above. Everyone in Rwanda knew that. And the country’s law for prosecuting génocidaires reflected that knowledge, imposing much heavier blame and harsher punishments on those who had operated from positions of power and influence than on the common folk who had physically performed most of the killing. But those leaders were strangers to Chantal. She could not accept that their responsibility for their crimes made her neighbor any less responsible for his. He had been the first person to kill on her hill. Nobody had ordered him to. He took the initiative. And the first person he killed was Chantal’s cousin. Chantal saw him do it. She was hidden in a nearby stand of eucalyptus trees, and from the moment her neighbor’s club came down on her cousin’s head, she said, “everything changed completely.” The hunt was on, and when it was over so was Chantal’s family. ”

Gacaca constituted the most ambitious and comprehensive exercise in accountability for crimes against humanity that any country has ever undertaken. In the course of 10 years, 160,000 citizen judges, in more than 12,000 jurisdictions, decided more than 600,000 cases relating to violent genocide crimes—killing, rape, and torture. Twenty-one percent of these were resolved by confession, 44 percent resulted in a conviction at trial, and 35 percent ended in acquittal. (By way of contrast, Rwandan officials liked to note that the UN’s International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda, which sat in Arusha, Tanzania, for 17 years, had convicted 61 individuals and acquitted 14, at a cost of about a billion dollars, which was roughly 20 times more than Rwanda spent on the entire gacaca system.)

One evening over beers in Kigali, while the trials were still in progress, I had a conversation about these conversations with a professor, yet another social scientist. “Gacaca got tripped up by a number of things,” he said. “And it created resentments beneath the surface—ethnic tensions mainly, familial tensions, too—which manifest themselves in the form of mistrust, in the form of suspicion and fear, in the form of rage.” The professor was sympathetic to these reactions. The confrontations of gacaca had made him deeply uneasy, too. But he had come to see it as “a necessary process” and ultimately “a good thing,” and he anticipated that, with time, much of the heavy residue of ill feeling that gacaca had churned up would be cleared away in gacaca’s wake. After all, the professor observed, gacaca’s project of determining individual guilt worked against the stigma of collective Hutu responsibility for the genocide, which Hutu Power had done so much to create, and which had kept Rwandans riven by mutual suspicion in the aftermath. “For a time, everyone was considered a génocidaire,” he said. “Now I think we’ve begun to breathe again.”

— Philip Gourevitch, The Burdens of Memory and Forgetting

Reconciliation remains an orphan in Bosnia, lingering in the shadows of a war that still haunts a traumatized population after more than two decades of peace. Hatred, by contrast, is its advantaged sibling. . . .Though the Dayton Accords ended hostilities on November 21, 1995, halting nearly four years of bloodshed, which had cost over 100,000 lives and had seen genocide committed for the first time in Europe since World War II, in many respects the conflict was frozen rather than finished. A generation after the fighting ceased, the driving forces behind the war—nationalism, separatism, and ethnic intolerance—not only remain but flourish, dwarfing chances for reconciliation and forgiveness, the two essential components to an enduring peace.”

As the overwhelming majority of the accused in Bosnia were Serbs, it became easy for the Bosnian Serb leadership to advertise the ICTY judgments as a conspiracy against Serbs, nullifying the ICTY’s hopes of reconciling through the acceptance of a common truth and instead rooting perception of the court in national myth. The leadership of the Bosnian Croats remained equally convinced that the court exaggerated its own lesser role in war crimes for political reasons. Meanwhile, many of the Bosniaks, conveniently overlooking their own side’s involvement in atrocities, focused instead on the greater criminal activities of their foes, defining their relationship with Bosnia’s Serbs entirely through the prism of the genocide committed against them. This was exactly the opposite of the ICTY’s original intent.”

Kemal pronounced the terms reconciliation and forgiveness with careful deliberation and nuance, noting that the first was a form of acceptance of the desire to live together again, utilising memories of what had happened in the war in an affirmative way. The term forgiveness, he added, involved a relinquishment of loathing in a process that began internally and progressed, eventually extending to those who had abused him in the Omarska concentration camp.

“You can’t reconcile with others unless you reconcile with your own past first,” he said. “You have to make peace with yourself and your own past. You choose. And it is a choice: Do I want to stay a victim for whatever reason, maybe because I feel more comfortable in that place, or because I am too afraid of a better life?”

— Anthony Loyd, God Won’t Have Forgotten

Psychology and neuroscience research have increased understanding of the legacy of violence and trauma on brains and bodies, which may help to explain why and how peace works or fails after conflict.”

— Elizabeth D. Herman, researcher and political scientist

“We know from research that living through a war, that having strong enemies, that being victimized actually changes the way you think,” said Mike Niconchuk, senior researcher at Beyond Conflict’s Innovation Lab for Neuroscience and Social Conflict. “Beyond the way you think, it changes aspects of brain chemistry; being a victim of conflict can affect the size of parts of your brain.”

“In neuroscience, studies have found that individuals with increased activity in the amygdala, the portion of the brain that governs threat awareness and fear responses, show increased distrust of out-group members. Thus, individuals who develop PTSD characterized by increased threat reactivity may be less willing to interact with individuals perceived as enemies, especially members of out-groups with whom they have engaged in conflict—precisely those with whom they may need to reconcile.

This neurological reality raises questions not only of how to build peace, but also of what kind of support individuals and communities may need as a foundation before they can really start to address the traumas of war.”

— Elizabeth D. Herman, It’s in the Mind: How PTSD affects peace

A third of the province’s population still suffer in some way as a result of the Troubles, with 200,000 experiencing mental health problems and 17,000 having post-traumatic stress disorder. Sixty-odd organisations dealing with trauma victims still receive thousands of referrals each year, and it is no accident that Northern Ireland has the UK’s highest suicide rate. Many more people —4,500— have killed themselves since the Good Friday Agreement than were killed during the entire course of the Troubles.”

— Martin Fletcher, Peace Without Harmony, on Northern Ireland

Dydine Umunyana, three and a half years old when she witnessed the Rwandan genocide, is the author of Embracing Survival. Her memories of narrowly surviving the genocide remain as fresh as the milk she carried on one fateful day, but the fright did not end there. While the killing stopped, the violence didn’t—she spent much of her childhood avoiding the anger of her traumatized father. Umunyana is now a motivational speaker, committed to establishing a dialogue between people for understanding their shared histories and cultural differences.

Post-traumatic stress disorder was not something many people in Rwanda understood. Instead we just talked of trauma. My dad had returned to Ruhengeri to save his family, but the entire family had been brutally killed. Nobody had survived. It seemed reason enough for a person to go mad, although my mother insisted that it wasn’t madness, that he was getting better.

“There is no life after this mass killing,” my dad would say, sounding like a very old man. “When I close my eyes at night, I dream the Interahamwe are here. I see them raise their machetes to kill my children. My only comfort is the thought that I can take my gun and kill us quickly, before they hack us to death.”

I was always puzzled by my father’s dark dreams. Why did he want us to die when we all had fought so hard to live?”

— Dydine Umunyana, Butterflies Sat Next to My Heart, on Rwanda

Plato, who knew a few things about violence and human nature, seems to have been right when he said, “Only the dead have seen the end of war.” Today, more countries are experiencing some form of violent conflict than at any other time during the last 30 years. And once wars start, they are unfortunately lasting far longer than they once did. In 1970, the average conflict lasted 9.6 years. Those that ended in 2015, the last year for which researchers with the Uppsala Conflict Data Program have analyzed the data, lasted 14.5 years.”

— Samantha Power, former U.S. ambassador to UN, Afterword

Conflicts produce devastating effects that go beyond the large-scale loss of human life and livelihoods. They often give rise to massive population movements, which are inherently destabilizing and which have incited a rise in xenophobia and nationalism across the globe. The movement of more than one million people, half of them Syrian, across Europe in 2014 and 2015 helped bring about a surge in support for right-wing populism; a repudiation of previous international norms providing for compassionate care and fair processing of those in flight; and a loss of faith in the European Union, which helped fuel support for the narrow Brexit vote in June of 2016”

— Samantha Power, Afterword

Samantha Power served as US Ambassador to the United Nations under President Barack Obama from 2013-2017 and has spent her professional life searching for ways to prevent egregious human rights abuses. Her 2002 book A Problem from Hell: America and the Age of Genocide explores U.S. responses to the major genocides of the 20th century, while her 2019 memoir The Education of an Idealist recounts her experiences trying to secure action to prevent and punish atrocities from inside government. She argues for scholars and policy makers to rigorously scrutinise both successful and faltering efforts to establish peace and to make far more substantial investments in diplomacy and conflict resolution at an early stage.

To step into the wake of the war against ISIS was to enter a dystopian world. As the circle closed in on the terrorist military group, first in Mosul, then in Raqqa, and then in their last redoubt in Baghouz, I traveled between newly liberated villages and cities. I went to document that vital moment between the end of a conflict and peace—the space where life begins to emerge. At first, everything seemed a blur of rubble, like a dark, smudgy water color of a never-ending nightmare about war and how it forever mutilates lives.

But, very quickly, the streets buzzed back to life. I witnessed civilians, so utterly traumatized, do the only thing they knew how to do: go on and survive. It was dark, yet remarkable, to see the cautious hope among people who had lost everything. They know: peace is so incredibly fragile. Unless the marginalization of peoples in each country is addressed, unless resolution is brought to disputed territories, unless the systematic corruption that hinders everything from rebuilding to job creation is ended, peace can once again unravel with astonishing speed.”

— Nicole Tung, photographer