In 1992, the fractured remains of Yugoslavia fully ignited in the Bosnian War, during which hundreds of thousands were killed and millions displaced in an ethnic conflict remembered for stark scenes of siege, massacres, and the return of genocide to Europe. The term “ethnic cleansing” is coined for the systematic expulsion, rape, and killing which would draw the world’s attention. In Imagine, photographer Ron Haviv and journalist Anthony Loyd revisit Bosnia some twenty-five years after they first covered the conflict. Predrag Kojovic, a Bosnian war time journalist and now a politician, breaks down the struggles contemporary Bosnia faces governed by the now decades old Dayton Peace Accords. Finally, Elvis Garibovic, a survivor of Keraterm death camp and depicted in one of Haviv’s photos which broke the story of its existence, reflects on his personal path to healing.

Imperial decrees tolerate a diversity of religions, but the empire brings the spread of Islam, forming the nations core ethnic group while maintaining Orthodox, Catholic, and Jewish sects.

Serbian Nationalists claim Bosnia as a Serbian province. Croatian nationalists similarly claim Bosnia as their own province.

This crisis is resolved at the Congress of Berlin, at which Ottoman power in Europe is diminished and the Austro-Hungarian Empire moves to annex Bosnia.

By killing the next in line for the Austro-Hungarian throne, Princip begins the chain reaction which will rapidly lead to World War 1

The nation is a constitutional monarchy. In Russia, the communists fight a brutal civil war with the czarists.

Over the next twenty years, he would rise through the ranks of the party, becoming acting General Secretary by 1937.

The Nazis utilize a Croatian puppet state which establishes the infrastructure of Nazi genocide in the Balkans.

The rebels, known as the Partisans, mount one of the most successful resistances to Nazi occupation in Europe, earning Tito’s Yugoslavia the recognition and support of the Western Allies and Red Army alike.

Each of the states contain a distinct ethnic group; Bosnia, in addition to being home to Bosniak muslims, also holds a significant mixture of Serbs, Croats, and others.

Tito, a Croat, maintains a tight grip over the six republics and the various ethnic groups who are now known as ‘Yugoslavs’. As an unaligned nation in the Cold War, they will be denied strategic and economic partners on both sides.

The power vacuum in the wake of his death leads to individual states within Yugoslavia vying for power.

Economic crisis causes accelerating shortages in consumer goods, forcing the ethnically-organized states to compete internally.

The 10-day war between Slovenian and Yugoslav forces ends in victory for the new and independent nation of Slovenia. Slovenia maintains her independence. A six month war breaks out between the JNA, the armed forces of Yugoslavia and the fledgling forces of Croatia.

The ban disproportionately affects Bosnian self defence capability. Serbian forces control large percentages of the former Yugoslav military, and Croatian forces seize their own arms upon declaring independence.

The newly minted nation contains three main ethnic groups: Croats, Serbs, and the majority, Muslims. Yugoslavia is now comprised solely of Serbia, Montenegro, and the disputed autonomous province of Kosovo. Despite this, the two states will continue to use the name Yugoslavia until 2003.

Republika Sprska announces their goal to unite with Serbia. The Army of Republika Sprska begins the siege of Sarajevo.

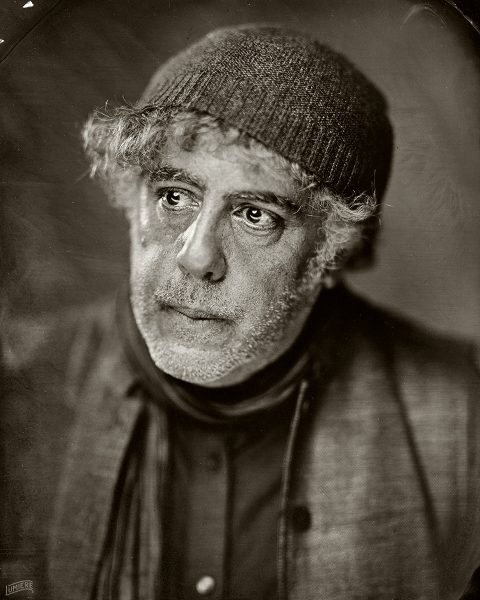

Ron Haviv is a photojournalist who produced some of his most notable work during the Bosnian conflict, where he was the first to document ethnic cleansing. He is a co-founder of VII photo agency and the VII Foundation.

Tensions were already high, and violence was breaking out in the town of Bijelijina on the Bosnian-Serbian border. The community quickly split along ethnic lines, and the hatred and barbarity that was to became normal during the years of this war began here: the banker fighting against the barber, the school teacher fighting against the grocery clerk. I was witnessing a complete breakdown of civil society.”

— Ron Haviv

The CIA and UN would estimate that Serbian forces were responsible for 90% of the war crimes during the conflict, with Croatian and Bosnian forces responsible for the remaining 10%.

Thousands of men are killed and tortured in Omarska, Manjaca, Keraterm and Trnopolje camps over a period of several months in the spring and summer of 1992.

A Bosnian Muslim from a village near Prijedor, Elvis Garibovic was picked up by Serb militia in April 1992 as the former Yugoslavia unraveled, before the world had heard of ethnic cleansing. He was subjected to extreme torture and deprivation in the makeshift concentration camps of Keraterm and then Trnopolje, in Serb-held northwest Bosnia. He now lives in Australia.

In Keraterm, a couple of days after the massacre, July 26, I had my 20th birthday, the moment I learned the meaning and the power of hope and will. I wasn’t prepared to gamble my life, so I started observing, learning, and evolving simply to survive.

I gave myself two weeks to live, as the starvation was causing my body to shut down.”

— Elvis Garibović

A day in a concentration camp is like a year of living normally. You witness major events each day, if you survive the day. You realize that you might be around for a few hours or a few days, so you make every moment count. You must answer the question, What kind of person are you?

“Later on August 5, there was a commotion. People were rushing to the barbed wire fence. We saw a reporter lady trying to talk to people. Cameras were rolling. In the following days, more photographers arrived, including Ron Haviv. Seeing them there, with two or three cameras slung around their necks, I decided to take my shirt off, in the hope that I would get their attention and have my picture taken. Then my family would know the last place I had been, if I were to disappear as countless others already had.

“I met a Bosnian man in New Zealand who was an Auschwitz survivor. I could share my story with him, and he could share his with me. Since then, I have found a new level of understanding for Jewish people and survivors of the Holocaust. We have seen the cruelty of one human being toward another.

To forgive someone who has sent you to hell takes a lot of inner strength. Why does the victim have to be the one to forgive? Does that make him the better person? In whose eyes? Or does that make him weak so they can do it again? I can’t see all Serbs as the same. As one is trying to kill me, another is saving my life.”

— Elvis Garibović, The Wolf You Feed

The UN determines to protect 6 ‘safe havens’ in Bosnia: Sarajevo, Tuzla, Bihac, Srebrenica, Gorazde and Bihac

Over a period of 24 years, there are 161 indictments resulting in 90 convictions.

It was the hope that holding individuals accountable would allow societies to move beyond collective guilt and start to repair themselves. This hope was complemented by a belief that such trials would deter aggression in the future and therefore advance the cause of world peace.”

— Justice Richard Goldstone, first chief prosecutor for the ICTY

NATO begins an active military role, enforces a no-fly zone and conducts bombing missions against Serbian positions.

“The ICTY did not prevent the continued perpetration of serious war crimes. Indeed, the infamous genocide in Srebrenica in July 1995 was carried out—on the orders of Radovan Karadžić (self-proclaimed president of the Republika Srpska) and Ratko Mladić (commander of the Bosnian Serb army)—a few months after it was publicly announced that war crimes charges were being prepared against them for crimes including genocide and crimes against humanity. The indictment was issued on July 25th.

However, the ICTY’s indictment of Karadžić in 1995 set the stage for a gathering near Dayton, Ohio, in the United States, in November of that year. This was the conference that produced an agreement known as the Dayton Accords. Had Karadžić attempted to attend the conference, the United States would have arrested him and transferred him to The Hague for trial. In effect, the indictment prevented an alleged war criminal from participating in the negotiations; this made it politically possible for the leaders of Bosnia and Herzegovina to attend. The Dayton Accords ended the war.”

Pressure from NATO and US negotiator Richard Holbrooke, bring all three parties to the table where a peace agreement is reached. US troops arrive as part of the NATO peacekeeping mission.

The Dayton Accords establish a tripartite power sharing agreement which, while intended as temporary, continues to govern Bosnia-Herzegovina to this day.

Predrag Peđa Kojović, a former journalist, is now the President of Naša Stranka (Our Party), and representative for Sarajevo in the national parliament.

Serving as a reporter for Reuters throughout the 1990s, Sarajevo born Pedrag Peđa Kojović returned to Bosnia and Herzegovina after several years abroad to found Nasa Stranka (Our Party). In 2018, he won a seat in the national parliament.

The following is excerpted from an interview with the VII Foundation on the legacy of the Dayton Accords.

Any agreement that stops the killings, the ethnic cleansing— in other words, the war—is an achievement worthy of praise. The Dayton Peace Accords, in that sense, deserves both our respect and our gratitude.

(However) Article IV created a legal, procedural, and political nightmare. BiH occupies less than half the territory of New York State, yet the constitution divided a simple prewar state into two state-like entities.

The Presidency of BiH comprises three people: a Serb from the Republika Srpska, and a Bosniak (Bosnian Muslim) and a Croat from the Federation. The position of president rotates every eight months among the three members. They have meetings where they vote on issues, and each of them has veto power. They each travel in a separate plane, drive in a separate motorcade, and have a separate little military welcoming unit.

Unless you publicly declare yourself as Bosniak, Serb, or Croat, you cannot run for the presidency of BiH, you cannot run for certain legislative bodies, you cannot be an elected professor at a public university, you cannot get a job of importance in public companies, and you cannot serve in some governmental agencies. Furthermore, if you are a Bosniak or a Croat but you live in the Republika Srpska, you cannot run for the presidency. If you identify as a Serb and happen to live in a part of the Federation, as I do, you cannot run for president either.”

“The fundamental error of the Dayton constitution, however, is the absence of ethics. The constitution legalized what the warring sides had achieved by military and criminal means—by the spurious policies of ethnic cleansing and war crimes, including the genocide in Srebrenica. After the war the Dayton Accords gave them an advantage, and ever since they have practiced politics as a continuation of war by other means.

“We were unfortunate to live in what Hegel called “congested history”—a time of major political tectonic shifts, of dramatic, large-scale, political, violent events. Ethnic cleansing, religious intolerance, state corruption, and nationalism filled the power vacuum after the fall of communism. History left all these things for the next generations of BiH as heavy, almost impenetrable obstacles to a better future.”

— Predrag Peđa Kojović The Perils of a Peace Imposed

But Enes’s voice wearied when he spoke of Bosnia’s segregated schools and the inability of members of each of the three main communities to reach beyond their own experiences to find common understanding. “No one is ready to criticize their own side’s actions in the war,” he said. “And with so much of schooling segregated, if conflict ever begins again, it will be much easier to form battalions along sectarian lines. Just march them out of class straight into their units.”

— Anthony Loyd, God Won’t Have Forgotten

The Bosnian Serb party expels all war crime suspects from Republika Srpska.

The mass grave, thought to hold over 600 victims of the Srebrenica massacre, is one of many.

His death months before the verdict of his trial raises suspicions of suicide or foul play, but no substantive evidence of either is found.

Amongst other charges, he was found guilty for the massacre of 37 muslims at Stupni Do.

Anthony Loyd is a British foreign correspondent for The Times of London and has been reporting from war zones since 1993, when he first traveled to Bosnia. He has written a memoir from his time in Bosnia My War Gone By, I Miss It So.

Walking through the aftermath of a massacre one autumn afternoon in 1993, I encountered three dead women, eyes open, staring outwards from the open trapdoor of a grain pit. One had been shot repeatedly in the chest, the other in the throat, the third in the mouth. They were bunched tightly together, seated shoulder to shoulder, and had linked their arms in comfort and solidarity to face their deaths.

All Muslims, they had been killed in an outhouse in the village of Stupni Do when Croatian HVO troops overran it on 23 October 1993. In total the troops slew 37 people in the ensuing massacre. The youngest victim was two years old.

What I did not know until much later was that there had been a survivor in that pit. In 2017, 24 years later, I sat in a café in Vareš, a run-down industrial town that had once been a major center for iron ore mining and steel production, and spoke with Mufida Likić, who as a 14-year-old girl had hidden beneath her 21-year-old sister, Medina, in the pit. Mufida had already been bleeding from a wound to her left leg, incurred when the troops shot her earlier as she ran for shelter. She lay concealed, wounded and in silence, as they slew her sister, along with her aunt and her cousin.

Mufida waited an hour buried beneath the dead, until she was sure the killers had gone. Then she scrambled from under the bodies and stumbled outside, moving uphill towards the forest, where she met up with other survivors.

Fourteen years later, she testified at The Hague in the 2007 trial of two Bosnian Croats, Milivoj Petković and Slobodan Praljak, both of whom the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia (ICTY) subsequently found guilty of multiple war crimes, including executive involvement in the massacre at Stupni Do. They were sentenced to jail for 20 and 25 years, respectively.”

— Anthony Loyd, God Won’t Have Forgotten

The family still keeps the photograph hidden in the bottom of a closet as testimony to the era’s darkness. Now married and a mother, Amela has consciously raised her own children to avoid the hatred of the war and speaks forcefully of her hopes for her children’s generation to break the cycle of sectarian division affecting Bosnia.

But the family also acknowledged the complexity of the word “forgiveness.”

What does it actually mean to forgive?” asked Atija. “Whom am I to forgive? Someone personally, or people in general? I would really like my former Serb neighbors to come back here, have coffee with me in my home, and talk honestly about what happened. It would be easiest for both of us. But that won’t happen. We are no longer in contact. The efforts made to divide us from each other succeeded in preventing us from speaking again.”

— Anthony Loyd, God Won’t Have Forgotten

Slow economic growth and the gridlock of tripartite governance have remained roadblocks to both of these goals. Both the IMF and World Bank rank Bosnia as having one of the lowest GDP per capita rates in greater Europe.