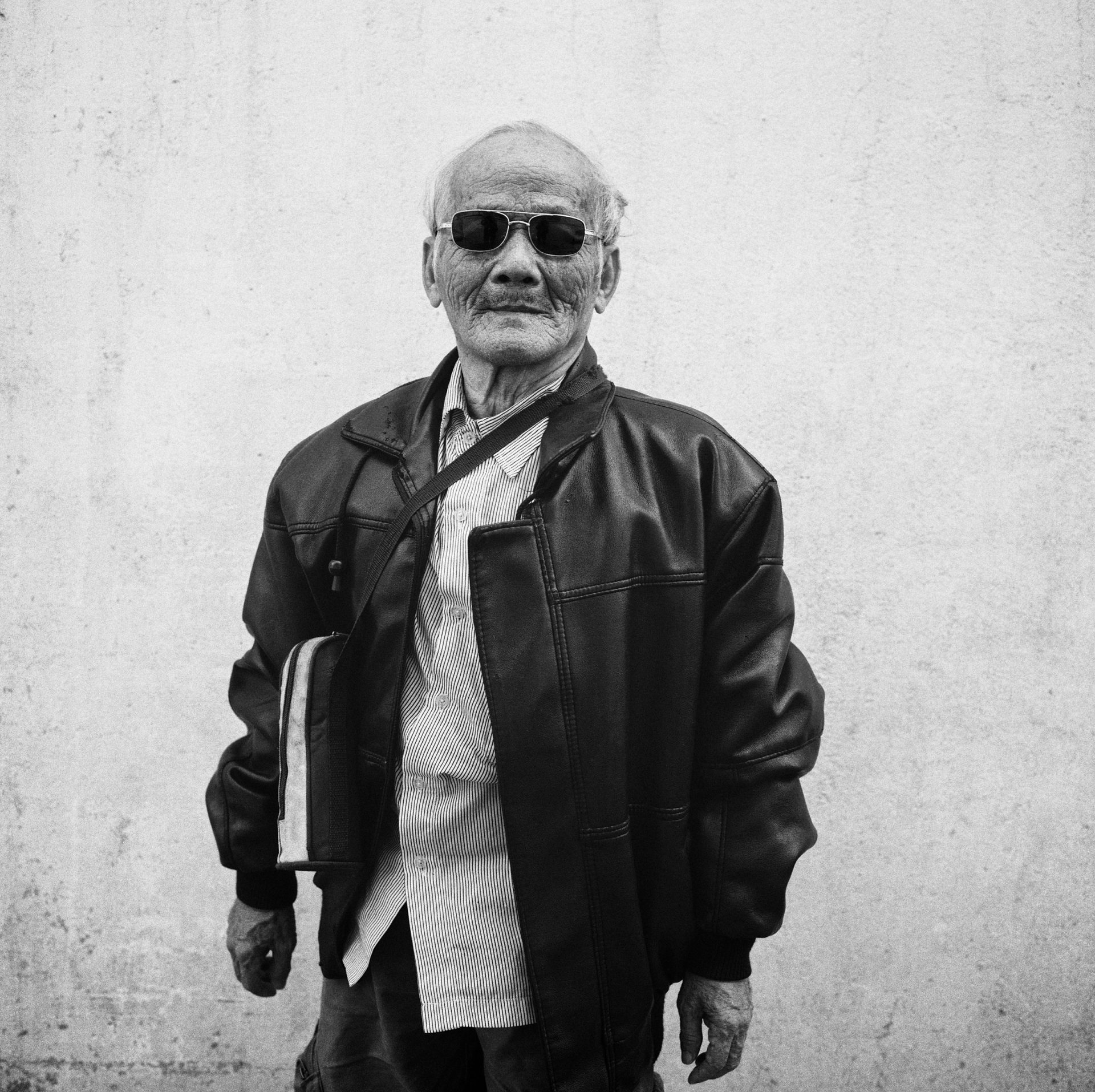

Back at the water festival, I had met an old fisherman, a genocide survivor, accompanying his granddaughter. He greeted me with a traditional Khmer sampeah—putting his palms together, with a slight bow of his head. He was still poor, his life much the same old struggle, but he immediately expressed pride and pleasure at seeing his king close up, and he rejoiced that Cambodians were no longer killing each other. “We Khmers don’t want any more violence,” he said. “We must unite together, listen to each other, or there will be no peace and no dignity. It is wonderful that we no longer hear gunfire. But peace is as fragile as a flower.”

— Jon Swain Fragile As a Flower

The Khmer Empire, at its height, rules from Burma to Vietnam. Cambodia is a highly evolved and advanced agrarian state and the capital, Angkor, is the largest pre-industrial urban center in the world.

In the Treaty of Saigon, they secure Saigon, a trade agreement, and the legalization of Catholicism.

While nominally securing freedom from Thai and Vietnamese incursion, Norodom cedes control over most functions of the state to the French as they begin building their colony of Indochina.

The French collaborate with the British to maintain European colonial control over the region. The French rule Cambodia, Vietnam and Laos.

During the last months of the war in the Pacific, the Japanese encourage individual South East Asian states to declare independence.

As the allies regain control of the Pacific, they restore French power over Indochina. The Khmer Issarak, a loose collection of anti-colonial factions, forms in Cambodia.

Communist Vietnamese forces beat the colonial French forces precipitating the dismantling of French power in Indochina and the end of French colonies worldwide

They study the writings of Marx, Lenin, and other communist revolutionaries. A working group of Khmer students forms to discuss Cambodian independence.

The Khmer Issarak divides roughly into a left wing, Communist faction and a right wing Royalist faction.

Under the leadership of Norodom Sihanouk, they use fraud and intimidation to secure parliamentary power. Across the border in Saigon, the first US Military Advisors arrive in South Vietnam and begin training South Vietnamese troops.

The Ho Chi Min Trail, a supply line from North Vietnam through Eastern Lao and Eastern Cambodia, begins to supply the rebels with arms to wage guerrilla war in South Vietnam.

In Cambodia, Pol Pot rises through the ranks of Cambodia’s organized communist party, and forges a powerful alliance with Mao’s CPC.

Sihanouk severs diplomatic ties with the US and expels communist leadership from Phnom Penh; Pol Pot establishes a base of operations for the Khmer Rouge in Northeastern Cambodia.

Sihanouk fails to balance a neutral foreign policy. He allows the North Vietnamese and VC to operate in Eastern Cambodia, while simultaneously permitting pro-American General Lon Nol to go after domestic communists.

Peasants fight back against Lon Nol’s forces as they crack down on illegal rice sales. The Khmer Rouge attempt to use this momentum to kick off a large-scale communist uprising, and begin small scale military operations.

Protests and crumbling morale threaten the war effort after a massive coordinated offensive by North Vietnamese and Vietcong begins on the Vietnamese holiday of Tet

Congress will not be informed for another four years.

Cambodian parliament grants Lon Nol emergency powers, which he uses to order all North Vietnamese and VC out of the country. The ousted Sihanouk flees to China, where he encourages resistance

State-sanctioned massacres of ethnic Vietnamese begin across Cambodia.

The former leader assumes nominal leadership of FUNK (National United Front of Kampuchea), a Khmer Rouge aligned rebellion government. Military operations are run by Pol Pot and Khmer Rouge hardliners.

American and South Vietnamese forces launch counter operations on Cambodian soil. The initial gains made by the North Vietnamese help secure Khmer Rouge foothold from which to fight.

Badly outmatched by the growing Khmer Rouge, Lon Nol tries to cease hostilities as the Paris Peace Accords are signed. The Khmer Rouge press on and gain further ground.

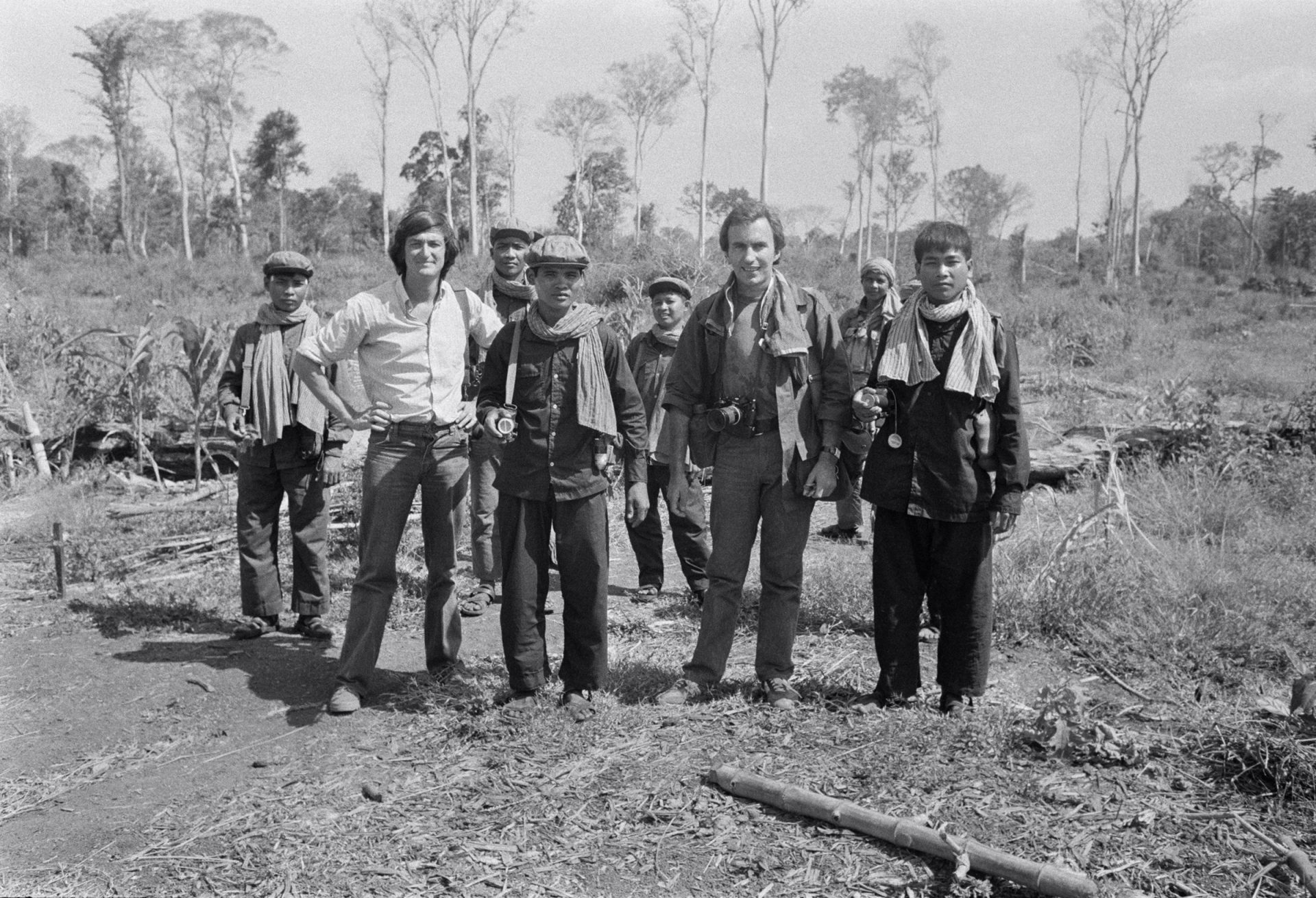

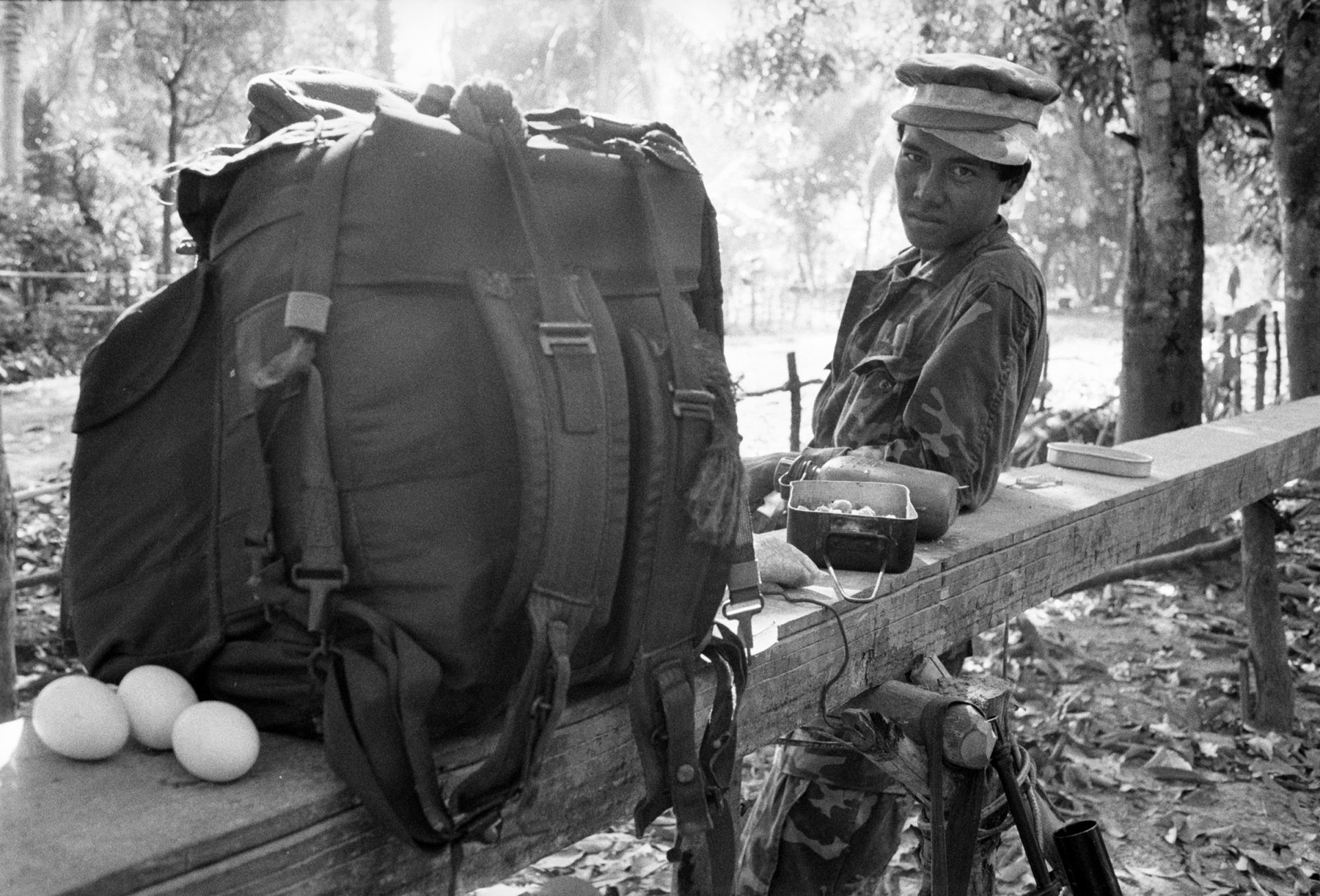

In 1973, I was a student in sociology in Brittany and was very motivated to experience the ills of our world firsthand. During the summer break, a friend and I dreamed of getting to Cambodia to hone our skills as burgeoning photographers. We managed to fly into Phnom Penh a couple of weeks ahead of the end of the US B-52 bombing of the country.

That for me was a revelation in covering a conflict, a big leap after trailing my camera along the student protests of the early 1970’s in France. It also became a jumping off point from university and the entry into a career as a photojournalist. Reporting that war became a passion, and with the fall of Phnom Penh to the Khmer Rouge on April 75, it altered my life forever.”

— Roland Neveu

Roland Neveu is a French photographer who photographed the fall of Phnom Penh to the Khmer Rouge in 1975

Sihanouk, having granted the Khmer Rouge early legitimacy, ceases to be useful. Pol Pot and his lieutenants seize full political control. A rift forms between Mao’s CPC and the USSR. North Vietnam has strong ties to the USSR, while the Khmer Rouge align with China.

Days later Saigon falls to the North Vietnamese. The Khmer Rouge evacuate the city. While Khmer Rouge atrocities were reported and witnessed with gradual escalation throughout the civil war, mass killing begins as they assume control of the country. Cambodia is now Democratic Kampuchea.

Executions account for at least a million deaths, while forced labor and second order effects of Khmer Rouge rule account for many more. It is the only genocide in history where a single ethnic group turns in on itself. The Khmer Rouge receive the support of China and Sihanouk.

My freedom now is not good and freedom is the most important thing for anyone, more than anything. I have the UN Treaty of Human Rights on my desk, I wish every country would follow that. The Khmer Rouge Tribunal has had limited success, they rejected the demands of the victims for compensation, and none of the aid that went to the tribunal went to the victims. I am very angry about that. We deserve compensation. Compensation is the most important part of justice and with no compensation there is no justice. Compensation could help the victims survive the peace”

— Bou Meng

As chaos begins to upend Khmer Rouge organization, a Battallion Commander named Hun Sen flees with his soldiers to Vietnam. There, he forms a partnership with the Vietnamese in preparation for invasion.

I was forced to join the Khmer Rouge in 1972 because my village was controlled by the Khmer Rouge. “In 1974 I was arrested by the Khmer Rouge because I was accused of being a spy for the Lon Nol regime. But I was set free because I was so young. That is the worst memory I could remember. I was serving them but instead they accused me of being a spy. We had very little to eat. I was so depressed. Between 1975 and 1979 I was forced to work as part of a mobile team working on irrigation and dam projects. “At that time, I was feeling that my life was in darkness with no hope of being alive. Everything seemed hopeless.”

—

Roeung Heng, former Khmer Rouge soldier

Hun Sen, a former Khmer Rouge, is appointed Foreign Minister and deputy Prime Minister. In 1985 Hun Sen is made Prime Minster, a position he retains to this day. The Khmer Rouge flees west and rebuilds inside Thailand.

Born into a peasant family up the Mekong River from Phnom Penh, he (Hun Sen) had, at the age of 20, joined the Khmer Rouge resistance against Lon Nol. Hun Sen lost an eye in the war. In 1977, as a battalion commander, he fled to Vietnam to escape the ever-deeper purges scything through Khmer Rouge ranks. As if from nowhere, the Vietnamese chose him as foreign minister of Cambodia, and then he became prime minister in 1985, when he was 32.”

— Jon Swain, Fragile As a Flower

The UN votes to recognize the Khmer Rouge, not the Vietnamese-aligned delegation, as the legitimate government of Cambodia. Pol Pot steps down as PM, focusing on the resistance effort.

The Khmer Rouge enjoys international recognition and begins to try to change its image. The KPNLF, a pro-western, anti-communist faction, is created by former politicians from the late 1960s Cambodian government. They are backed by the Thais, and later, the US. Sihanouk forms FUNCINPEC, a royalist faction which collaborates with the Khmer Rouge. The three groups form a government in absentia and use UN supported ‘Displaced Persons Camps’ on the Thai border with Cambodia as bases for their soldiers and their families.

Jon Swain was the only British journalist on the ground in Phnom Penh when it fell to the Khmer Rouge in April 1975. The British Press Awards named him Journalist of the Year for his coverage of that event. His character was depicted in Roland Joffe’s Oscar-winning film The Killing Fields. Swain was a staff correspondent for many years at the Sunday Times of London.

In early 1980, I returned to see the entire nation on the move—people were trekking to refugee camps in Thailand or returning to the homes from which they had been uprooted. They were searching for their loved ones and scavenging for food. Phnom Penh was a wasteland of decaying and melancholy buildings, populated by traumatised people desperately trying to rebuild their shattered lives. In vain, I searched for people I had known and loved. I visited their abandoned homes. They were empty and full of ghosts. I found only one friend from the past, a once-delicate city girl whom the Khmer Rouge had turned into a rough peasant. Her hair was clipped short, her coppercoloured skin had coarsened in the sun, and her beautiful hands were covered in sores. “Maman morte, bébé mort,” she said with a look of profound sadness.”

— Jon Swain, Fragile As a Flower

The Khmer Diaspora, began in the 1970s, scatters Khmer communities throughout the world, including Thailand, France, the US, and Australia.

Gary Knight is a photographer and the principal architect of the VII Photo Agency. He is the co-founder and director of the VII Foundation and the president and founder of the VII Academy in Arles, France, and Sarajevo, Bosnia. He began his career photographing in Southeast Asia in the 1980s.

I arrived in Cambodia in 1989, more than a decade after the Khmer Rouge had embarked upon its three years of slaughter, rewound the clocks to Year Zero, and taken the country back to the Middle Ages. The extent of the genocide they had perpetrated was exposed when Vietnam invaded Cambodia in 1978 and drove the Khmer Rouge over the Thai border. The remnants of their army were fed in the United Nations ‘displaced persons’ camps along with hundreds of thousands of starving civilians.

Within weeks of the arrival of these decommissioned troops, ruthless Realpolitik took over, and the Thai, Chinese, American, and European governments, resentful of the Vietnamese, rearmed and rehabilitated the Khmer Rouge and created an alliance of guerrilla groups to fight Vietnam in Cambodia.”

— Gary Knight

The agreement gives the Cambodian people the right to fair and free elections and establishes the UN as a transitional authority, UNTAC.

UN forces clash with the Khmer Rouge as they massacre ethnic Vietnamese and refuse to participate in elections.

FUNCINPEC and Hun Sen’s Cambodian People’s Party (CPP) form an uneasy coalition. Khmer Rouge opposes elections.The royalist FUNCINPEC, led by Sihanouk’s son Norodom Ranariddh, creates a government with Hun Sen after he threatens to lead Eastern Cambodia to secede from the rest of the nation.

In subsequent elections in 1998, the CPP firmly controls the majority of the coalition government with FUNCINPEC and the newly formed SRP. Pol Pot dies in a Khmer Rouge camp in the North West.

To Western eyes, the preservation of Pol Pot’s cremation site is wrong. He was responsible for one of the worst mass killings in modern times. But Cambodians reason differently. Even survivors express approval. Still, I was surprised by the response of a teenage girl passing by Pol Pot’s grave when I visited. “Pol Pot was trying to do something good for Cambodia and was betrayed by Ta Mok,” she said to me.

“For Cambodians it is preserving evidence that is important,” said Chhang. “It is the fear that the world will not believe. The gravesite is just to show Pol Pot lived here, Pol Pot died here. It is evidence, and people do not want it removed.”

— Jon Swain, Fragile As a Flower

A tribunal, called the ECCC, is formed and begins, backed by the UN and lead by Cambodian and international judges.

A most important lesson to be learned from the history of the international criminal courts and tribunals is that victims of massive crimes cry out for, and indeed demand, some form of accountability and justice. If that call is thwarted, there will be a cancer in that society which, sooner or later, will manifest itself in further cycles of violence. The history of the Balkans and Rwanda provides evidence in support of this assertion. To that extent, at least, justice mechanisms have helped maintain peace in a number of postwar societies.”

— Justice Richard Goldstone, No Mere Postscript to War: The Role of International Criminal Courts

Several international judges quit the ECCC claiming that their Cambodian counterparts are blocking investigations of former Khmer Rouge members.

More than three decades later, Hun Sen is still in power, having outmaneuvered all his opponents. Although his long rule has been defined by repression and controversial election victories, the strongman is also recognised by many older people as Cambodia’s saviour from the genocidal Khmer Rouge regime (to which he had nonetheless once belonged). He has always denied complicity with the regime and warns regularly that only his leadership stops Cambodia from returning to civil war.”

— Jon Swain, Fragile As a Flower

The CPP holds onto power despite a close and disputed election. Protests form, which Hun Sen puts down with violence. He exiles opposition leaders and shuts down opposition new media.

By 2017, NGOs estimate that roughly half of left-over ordinance throughout the country has been identified and disposed of. Mines and ordinance continue to injure and kill every year, as well as making otherwise useful farmland unusable.

When I walked to school, I saw anti-tank mines. When I was seven or eight years old, coming back from school, I would run, play; I had no idea. Then a man in my village got exploded by an anti-tank mine. A lady lost two sons. So she became—well, her brain was not good, because she lost two sons. When they carried the second son’s body to the village for the funeral, I saw the relatives cry, and I saw a piece of the body and I felt very sad. But because I was young, I didn’t know what to do.

I started to learn more about how many land mines and unexploded ordnance there are in Cambodia and how many people they kill. I decided I wanted to be a de-miner.

In my training class was a general. The first day, there were only two women out of about 20 students. The men were like, “What? You are a girl, you come and do this job?” We were a joke to them. During the training, you had to role-play. Me and the general—he wanted to be number one, I wanted to be number one. So we fought very hard in the class. When we role-played, one day he is my team leader, the next day I am his team leader. I ordered him to do this, do this, do this, and then he said, “Oh, I understand.” Even though I am small and I am a girl, he saw that I wasn’t a joke. In the end he was number one in the class and I was number two. In 2011, I became a qualified de-miner.”

— Sophary Sophin, Excavating the Past, Imagining a New Life

“On average, women experience war differently from men. While men are more likely to take up arms and die on the battlefield, women are more likely to be responsible for caregiving during and after conflict, and they die at higher rates from human rights abuses, the breakdown in social order, and economic devastation.”

— Marie O’Reilly, The Essential Presence of Women in Peace: The Liberian Example

Hun Sen’s dynasty is secured in the legal institutionalization of his authoritarian power.

Manet continues to be groomed by the CPP to take over after Hun Sen retires

The terrible destruction wrought by a US B-52 bomber which had mistakenly dropped its 30 tons of bombs on the main street of Neak Leung during the Lon Nol war, killing and wounding 400 people, had long been covered up by new buildings, and the town was flourishing. But the human cost of Cambodia’s wars was easy to find amid this new prosperity. After we had been speaking for a few minutes, we encountered Heng Sokha, 55, an amputee begging in the street for money. He stood on his one good leg and supported himself with a crude wooden crutch as he held out his faded army cap for money. Conscripted at the age of 23 into Hun Sen’s army, he had been sent to the border with Thailand to fight the remnants of the Khmer Rouge who had retreated there after the Vietnamese invasion.

Shrapnel from an exploding artillery shell had smashed his leg. He had a hopeless air. As with the former Lon Nol soldier, his life had not improved in peacetime, despite his having given a leg for his country. His government pension of 400,000 riels a month (about $100) was not enough to live on. To survive, his wife was selling corn at a street stall.

“My children do not want me to beg for money, but I am desperate,” he said. “If I do not beg, I do not have enough money to buy medicine. I do not know how to make money. I only had three years’ education.”

— Jon Swain, Fragile As a Flower