Lebanon has endured decades of sectarian struggle, bitter internecine conflict, bloody vendettas, suicide bombings, invasions, and wars.

Since its independence in 1943 from France’s Mandatory rule, Lebanon’s fragile governance has been based on its National Pact, a complex division of power granting preferential status to the then majority Maronite Christian community, over its Shiite, Sunni, and Druze citizens. The rationale for this was Lebanon’s 1932 census, the only official census conducted to this day.

The 15-year conflict in Lebanon actually featured many wars. It erupted, on April 13, 1975, in a hail of bullets fired by a Christian militia and Palestinian gunmen in tit-for-tat ambushes. Most of the first victims were civilians shot while standing in front of a church or riding on a public bus. The war in the little Levantine country, which is about the size of Connecticut, eventually spilled across borders, then continents. More than a dozen local militias and the armies or interests of foreign governments on four continents were sucked into the strife. Like most conflicts, it proved easier to start than to stop.”

— Robin Wright, The Fire Under the Ashes

Maronite Christians, Sunni Muslims, and Druze vie for supremacy. In the 1800s, European powers begin to back ethnic groups as proxies for influence in the region.

An intricate web of conflicting alliances collapses into war with the assassination of the heir to the Austro-Hungarian empire. The Ottomans systematically kill an estimated 1.5 million Armenians.

The secret treaty, signed by Great Britain and France creates the nominal states of Syria, Lebanon, Palestine, Jordan, and Iraq.

The British take control of Iraq, Palestine, and Jordan, while the French take Syria and Lebanon. The British renege on their promise to the leaders of the Arab revolt.

Population of 875,000 40% is muslim and 58.7% christian

Lebanon becomes an important logistical hub for the war in North Africa.

Confessional System is established – based on the National Census of 1932 allocating political positions of power according to demographics:

President – a Maronite christian

Prime Minister – a Sunni muslim

Speaker of the Chamber of Deputies – a Shia muslim

Political power sharing traditions become institutionalized

Lebanon is a founding member

As hundreds of thousands emigrate to British Palestine, the UN begins to create a partition plan for Palestine which would create two states.

The Arab-Israeli war displaces 700,000 Palestinians in what is known as the Nakba or ‘catastrophe’

My father left Palestine at 20 years old, during the Nakba, the exodus of 1948. He said that all the people living in the Sheikh Dannun village, located in Akka (also called Acre), the ancient port city in Palestine, started running, most of them without shoes. They were fleeing bullets and fire coming from Israeli soldiers. My uncle stayed in the village, hiding himself in an old cave. My father couldn’t manage to do that; he just wanted to walk away. When he described the village, my father said it was all gray—gray because of fire and screams and dead people all over the place. My father said he kept walking for days until he arrived in southern Lebanon. For a while, he and others slept in valleys there.

After a huge struggle with all this fear of death and the unknown, my father finally arrived in Beirut, with not one penny in his pocket. There he and the people he was walking with found an empty area with no houses around. One of the old men said, “We’ll stay here for a while.” People close to the area gave them food and some blankets to sleep. They all thought they would go back after one week. It didn’t work like that. The one week lasted for 70 years.”

— Mira Sidawi, I Am a Refugee, just like Superman

Mira Sidawi graduated from the Lebanese University with a diploma in theater. A Palestinian actress, writer, and director, she has acted in a number of short films and feature films including Permission, Instead of a Homeland, and Mon Souflé. Most recently she has turned to directing. Her film The Wall uses wit and a sharp eye to tell the story of life in the Palestinian camps.

Christian President Camille Chamoun attempts to keep Lebanon aligned with the west as Arab nationalism sweeps across neighboring nations. US President Eisenhower intervenes diplomatically and militarily, securing a contentious election and transition of power.

Israel captures the Gaza Strip and Sinai Peninsula from Egypt, the West Bank from Jordan, and the Golan Heights from Syria.

A series of hijackings leads to a brief explosive conflict between Jordan and Arafat’s PLO, bolstered by Syrian allies.

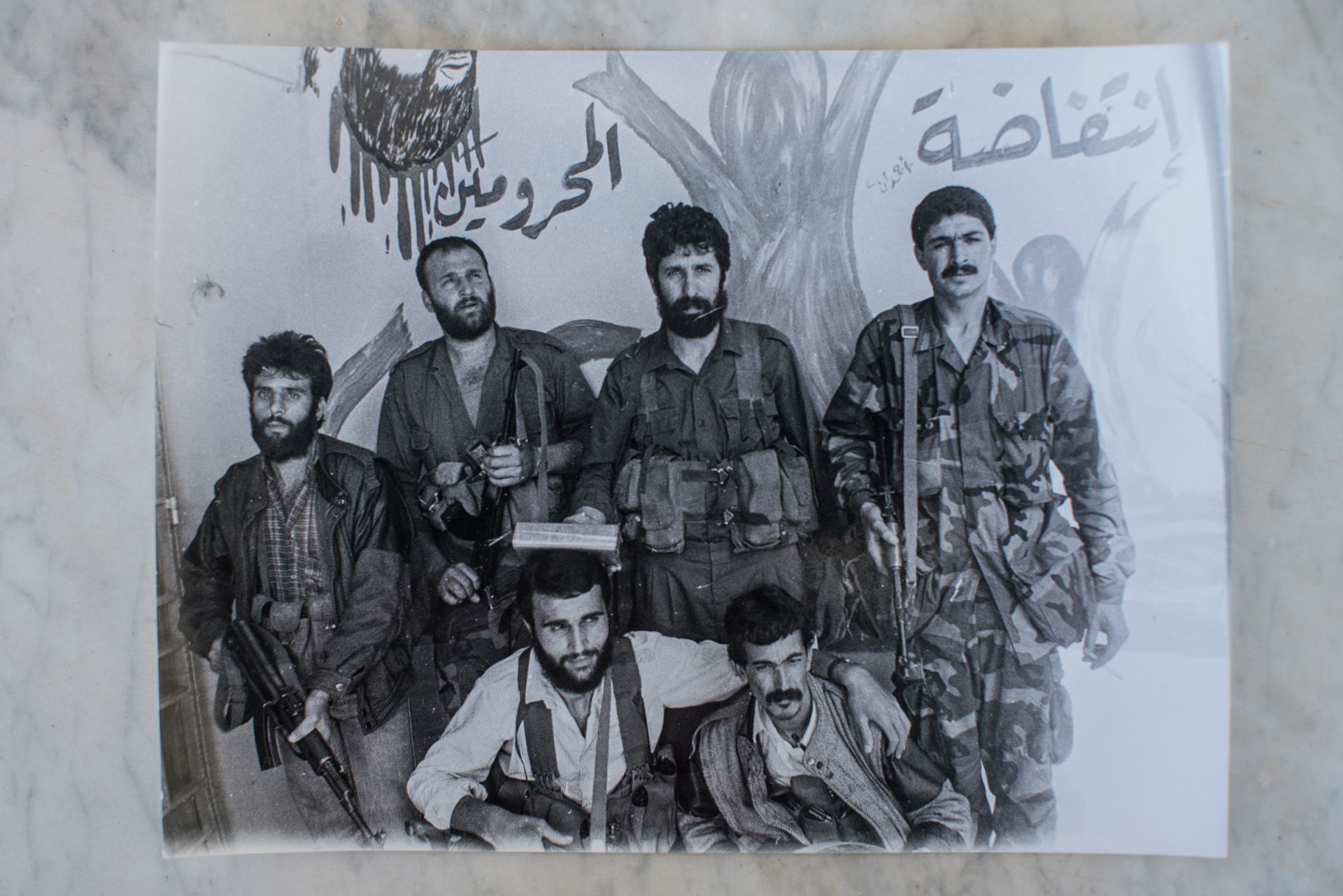

Lebanese sectarian militias begin to organize. Two main factions organize into a pan-Arab, muslim side supporting Palestinians and a Maronite Christian side. Each side is a loose coalition of militias with both secular and religious sub-groups.

Hard-line Maronite Falangists attack and kill 30 Palestinians on a bus. Political dissension grows over Palestinian operations waged against Israel from within Lebanon. The Lebanese National Movement (LNM) want more power for muslims. The Green Line divides muslim West Beirut from mainly christian East Beirut.

Known as the Karantina Massacre, the PLO respond by killing hundreds of Christian civilians in Damour.

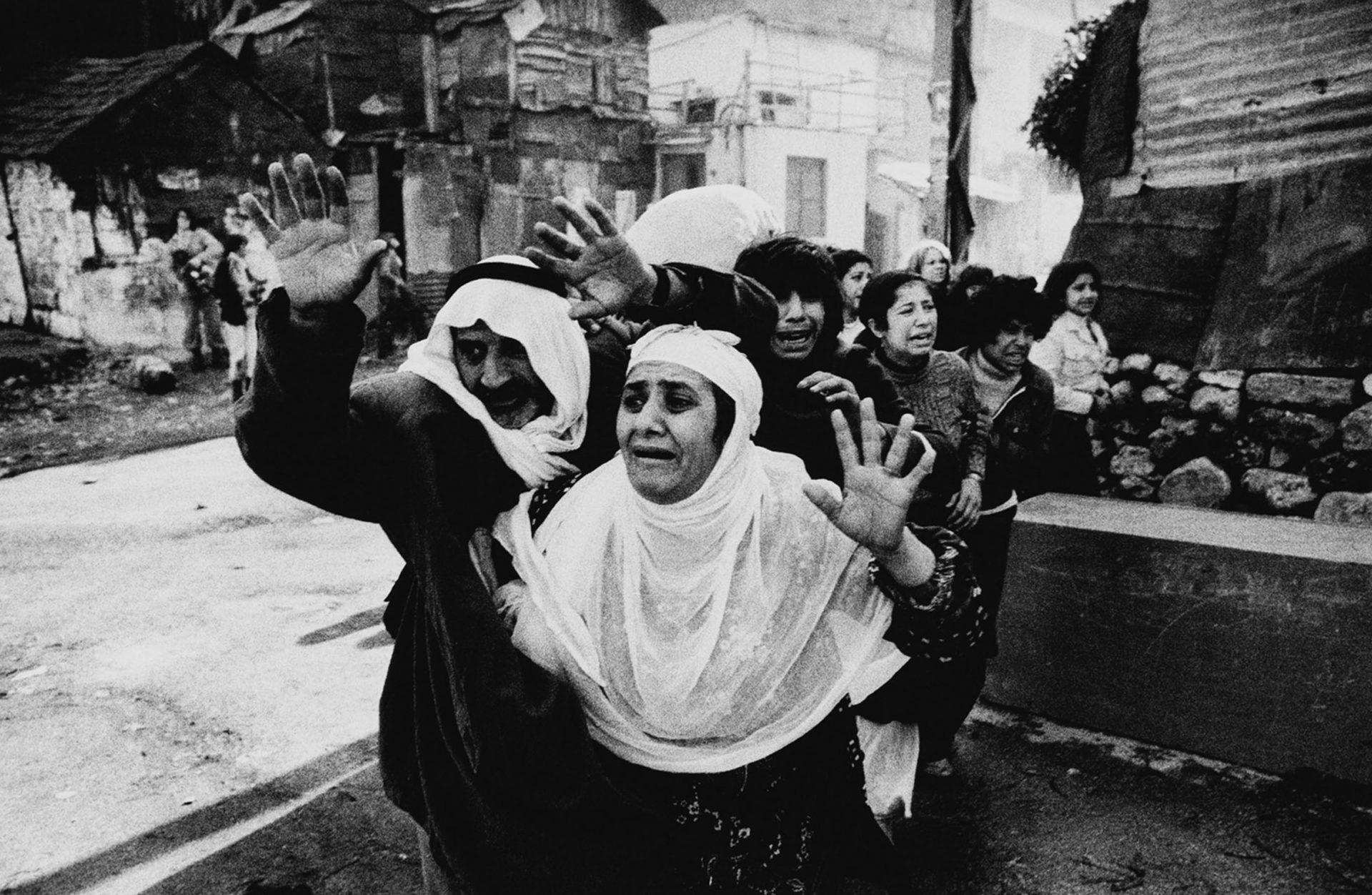

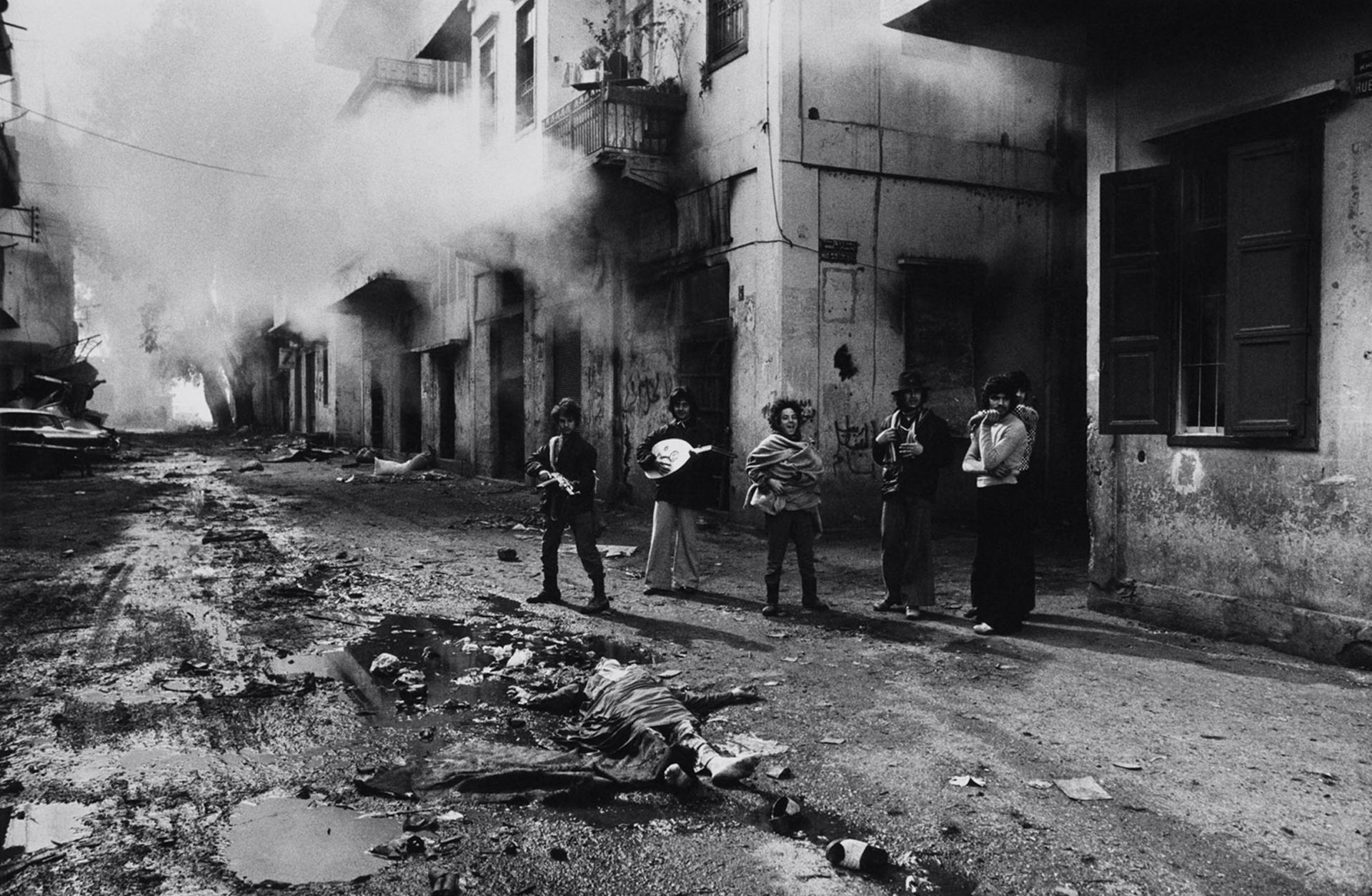

Don McCullin was photographing in Lebanon in 1976 when upto 1500 Palestinians were murdered in a massacre in the Karantina district of Beirut. He returned to Lebanon many times to document the civil war, paying particular attention to the displaced and dispossessed.

I went running with the first wave. It was evening and raining hard. They all wore hoods. We stopped behind a low wall and watched people being shepherded out of a hospital for the insane. People came to the windows of one wing. One of the Falange fighters shouted and when he didn’t get a proper answer he shot a burst of automatic fire into the window.

There was the same snip-snap of sniper bullets in the morning. Everyone seemed to have shrunk in the center of Karantina. An old American truck, like a Dodge pick–up, was brought up with a huge 50mm machine gun mounted on it. The Falangist on top was pouring out fire indiscriminately.

It was more than frightening, it was catastrophically fearful, like the dawn of a new dark age. I photographed, and went on photographing. I had pictures that would tell the world something of the enormity of the crime that had taken place in Karantina.”

— Don McCullin, Unreasonable Behaviour: The Updated Autobiography, London: Jonathan Cape, 2015

Arab Deterrent Force briefly calms the conflict before Christian militias mount a full-scale retaliation against the Arab forces in Beirut.

Falangists kill fellow Christians in the Safra massacre, as they attempt to consolidate control of the Christian factions.

US Diplomat Philip Habib organizes a truce. The agreement calls for the withdrawal of both PLO and Israeli elements from Lebanon, to be enforced by a coalition of American, French, and Italian forces. The PLO were evacuated by ship to Tunisia and overland to neighbouring Arab states. The Israelis retreat to the south but remain in southern Lebanon.

Wars often perpetuate themselves, albeit in new forms, with new types of fighters, new tactics, and new flashpoints. The original cause can be superseded, even dwarfed, by a conflict’s unintended consequences. Such was the case with Hezbollah. The Shiite Party of God did not emerge until seven years into Lebanon’s civil war, as the PLO was leaving.

Israel’s interventions, first in 1978 and then, in fuller force, in 1982, were by-products of the civil war. As the Lebanese state grew weaker, the PLO grew stronger. It launched border raids and lobbed shells into Israel. Israel’s first invasion forced the PLO farther back and created a buffer zone inside Lebanon—manned by a local Christian militia armed, trained, and subsidized by Israel—in 1978. The PLO persisted. In 1982, Israel returned, cannons blazing. It marched all the way to Beirut. It ended up staying in Lebanon for the next 18 years.

Lebanon’s Shiites, who populated the south, initially welcomed the Israelis. The Palestinians had usurped local power and endangered their homes by targeting Israel. Shiites were getting killed and their property destroyed for a cause not their own. When the Israelis rolled in, the local community greeted them with rosewater and rice. Then Israel lingered long after the PLO had left. Lebanon’s Shiites began to resist. And they got help, from Iran, further widening the war.”

— Robin Wright, The Fire Under the Ashes

Sabra and Shatila camp massacres by Christian Falangists

An estimated 3500 mainly Palestinian civilians are murdered in the Sabra and Shatila refugee camps while Israeli troops stand by.

The camp is like an ant’s world. Small alleys, tight houses, lots of pigeons all over the houses’ roofs. You might say that we Palestinians are the victims of the victims. But that doesn’t mean we can’t breathe or dream. I refuse to be the kind of victim who can survive on the happiness and choices of others.”

— Mira Sidawi, I Am a Refugee, Just Like Superman

I live this struggle every day: I wake up and wonder what I will have to do today to find inner peace. I have passed through a lot of angry moments. I remember that I have lived my life like a handicapped person, that I want to go back to my land. I remember my father and grandfather, who have nothing. I ask, Why does he have the right to take my land; why can’t he accept me? Anger is like a sword that kills you. Anger is not a language. Anger must be redirected as energy. I do yoga, I meditate, I pray. Being a refugee allows you to dig deep inside to find satisfaction.”

— Mira Sidawi, I Am a Refugee, Just Like Superman

Four young refugees plan to produce a film about Shatila Camp that should convince Roger Waters, the lead singer of Pink Floyd to visit their camp and perform there. The film follows their hilarious and sometimes dangerous adventures, uncovering the complex layers of living as a Palestinian refugee in Lebanon. The Wall is directed by Mira Sidawi

This was later seen to be the first Islamist attack against a US target

The largest number of Americans killed on foreign soil since WW II. The US begins to withdraw from Lebanon as bombings continue.

Ties between Lebanon and Iran dated to the 16th century when Iran converted to Shiism, with help from Lebanon’s clerics, to hold off the encroaching Ottoman Empire. In 1982, Tehran dispatched 1,800 Revolutionary Guards to help its Shiite brethren. They didn’t fight Israel. Iran instead culled defectors from Amal—which fragmented after Musa Sadr’s disappearance—and trained, armed, and organized them. The underground cells were the nucleus of what evolved into Hezbollah, the Party of God. They changed the nature of modern warfare—in Lebanon and far beyond—by introducing the jihadi suicide bomb. Faceless drivers rammed trucks laden with thousands of pounds of explosives into an Israeli headquarters, the American embassy in Beirut, U.S. and French peacekeepers, and then a temporary American embassy that replaced the first one. Hezbollah’s 1983 attack on the Marine peacekeepers produced the largest loss of U.S. military life in a single incident since World War II. The Marines slinked out of Beirut in 1984; the risks of staying were too high. Israel hunkered down in the south.”

— Robin Wright, The Fire Under the Ashes

Syrian backed Shia forces together with Lebanese army attack Palestinian refugee camps as Michel Aoun attempts to unite Maronite factions.

It took more than two years to track down Hamieh in the mid1980s. I found him on an intravenous drip, recovering from an injury, in the maze of Beirut’s poor southern suburbs. With his good arm, he was rocking a small hammock holding his six-month-old son, Chamran. Amal commandos ringed the small room. Hamieh had a following across the Middle East. He had accompanied Ayatollah Khomeini when the revolutionary leader flew from exile in Paris back to Tehran in 1979. He’d fought against Saddam Hussein’s army during the Iran-Iraq war. His fighters nicknamed him “Hamza,” after the Prophet Muhammad’s uncle, a famed warrior in the Islamic empire’s early days. We talked for hours about why men fight. He was a prototype.

“I see the future of my people determined by blood,” he told me. He compared Lebanon’s Shiites to South Africa’s blacks under apartheid. “For myself, I don’t have any future except to stay a fighter.” He gestured toward his son. “I hate to see him live as a slave. My child has the right to live well, to go to university. He has a right to be equal.”

— Robin Wright, The Fire Under the Ashes

The Arab League together with Lebanese parliamentarians broker a peace accord in Taif, Saudi Arabia, that makes way for political reforms. The agreement also calls for Syria to withdraw troops, and for Lebanon to reestablish control over all of Lebanon.

Robin Wright is an American journalist and author. She lived in Beirut during Lebanon’s 15 year civil war and watched it play out over local sectarian strife, religious rivalries and Cold War tensions. Wright returns to Lebanon to find the familiar faces who made headlines in the 1980’s and 1990’s. She also finds a new generation struggling to create a post-war society. Lebanon today underscores the challenges of reconstructing a riven society.

A quarter century after the war ended, the underlying tensions had not changed. Lebanon was without a president for more than two years, between 2014 and 2016. It had no new budget for a dozen years. Garbage wasn’t collected for months in 2015 and 2016 as rival politicos vied for contracts—for friends, relatives, or supporters—and rejected garbage being dumped on their turf. Sectarianism survived partly because of its patronage system. Bulging plastic bags of debris just piled up, consuming streets, fields, and public property. Pilots protested as birds scavenging near the airport endangered flight paths. Doctors warned of surging disease.

The garbage crisis galvanized the postwar generation. In 2015, the aptly named You Stink movement mobilized more than a hundred thousand people—from all faiths—in protests that lasted for weeks during the stench-filled summer. It took more than eight months to broker a compromise to end the rubbish rebellion.

Jean Kassir was part of the You Stink movement. He headed a student group headquartered at the American University of Beirut. “When you’re in the street demanding change, you realize it’s like asking a drunk person to fix the problem of alcoholism,” he told me. “He’s not going to help because he’s the issue.”

— Robin Wright, The Fire Under the Ashes

Israel continues military action in southern Lebanon against Iranian proxies.

In early 2005, 15 years after the war ended, Lebanon became the first Arab country to witness a popular uprising. The Cedar Revolution—the cedar decorates Lebanon’s flag—was sparked by the assassination of former Prime Minister Rafiq Hariri, a wealthy businessman who had returned from exile in Saudi Arabia to help reconstruct his country after the war. He was killed on Valentine’s Day in a car bombing as his convoy drove past the Saint George Hotel on the Mediterranean coast. The murder triggered mass protests for 10 weeks. At their height, more than a million people—roughly a quarter of the Lebanese population—rallied in downtown Beirut. They demanded the government’s ouster, an end to the 30-year presence of Syrian troops, and an international tribunal to investigate the Hariri bombing.

They prevailed. The Lebanese government fell; new elections were held. Syria was forced to withdraw troops that had been deployed—initially as “peacekeepers”—since shortly after the civil war began. And the United Nations established a special tribunal.”

— Robin Wright, The Fire Under the Ashes

Nichole Sobecki is a photographer based in Nairobi, Kenya. As a member of the VII Photo Agency, she aims to create photographs and films that demand consideration for the lives of those represented— their joys, their challenges, and, ultimately, their humanity.

Lebanon is where I came into being as a journalist. As an intern at The Daily Star—the Arab world’s storied English language rag—I published my first photographs. I even wrote the horoscopes briefly, confounding my friends with the specificity of their fortunes. In 2007 I saw war for the first time, as a battle broke out in the northern Palestinian camp of Nahr al-Bared. Fighting between the Islamic militant organization Fatah al-Islam and the Lebanese army began the morning of my 21st birthday. Though violence in Syria and other areas of the Middle East has since overshadowed the destruction of Nahr al-Bared, it was the most severe internal fighting Lebanon had seen since the civil war.

In 2017 I returned to Lebanon with writer Robin Wright to try to make sense of what peace means in a place so defined by conflict. As we met with former fighters and young creatives, I thought back to one of Aesop’s fables, “The Oak and the Reed,” and the countless storms this country has weathered without breaking. Peace here comes in shades of gray. It’s the reason to bend with the next wind, to endure, and to embrace the present despite the fire under the ashes”

— Nichole Sobecki

It will go on to indict individual members of Hezbollah in abstentia.

The Lebanese Army fights ISIL while Lebanese political factions debate which side to support in Syria.

Saad Hariri is the son of assassinated former PM Rafik Hariri.

Pro-Iranian, Shia groups accuse Sunni Saudi Arabia of holding Hariri hostage and forcing his resignation. An odd coalition forms between Shia and Sunni groups in Lebanon mutually calling for Hariri’s freedom. Hariri returns to Beirut and promptly rescinds his resignation.

Since 1948, UNRWA estimates over five million Palestinians have been displaced.

I will always imagine the country I deserve. It stands freely embracing poor people, tired ones, artists, mothers, children, and all of humankind. I believe in justice more and more, as I dream of getting rid of all walls that separate humans from each other. But living in these hard conditions and questioning peace, or writing about peace, is itself a kind of peace.”

— Mira Sidawi, I Am a Refugee, Just Like Superman