In 2018, the VII Foundation asked more than a dozen renowned reporters and photojournalists to revisit countries with which they had become achingly familiar during times of brutal conflict. The task was to see peace through the prism of their journalistic experience; to survey familiar towns and villages; to reconnect with women, men, soldiers, civilians, statesmen, and students who had survived the conflict or grown up in the postwar society; to discover what the lived experience of “peace” feels like. To augment this reportage, we sought input from academics and peacemakers. And we invited citizens of those countries to give their very personal narratives, in their own voices. Hard edges were not softened nor unpalatable impressions deleted. We wanted to show the truth as seen and experienced by those that lived and those that reported on seemingly intractable civil wars in Bosnia and Herzegovina, Cambodia, Colombia, Lebanon, Northern Ireland, and Rwanda.

The result is Imagine: Reflections on Peace—a curation of searing images and trenchant essays that show both micro and macro views of peace, with its uneven degrees of economic success, political stability, and social harmony.

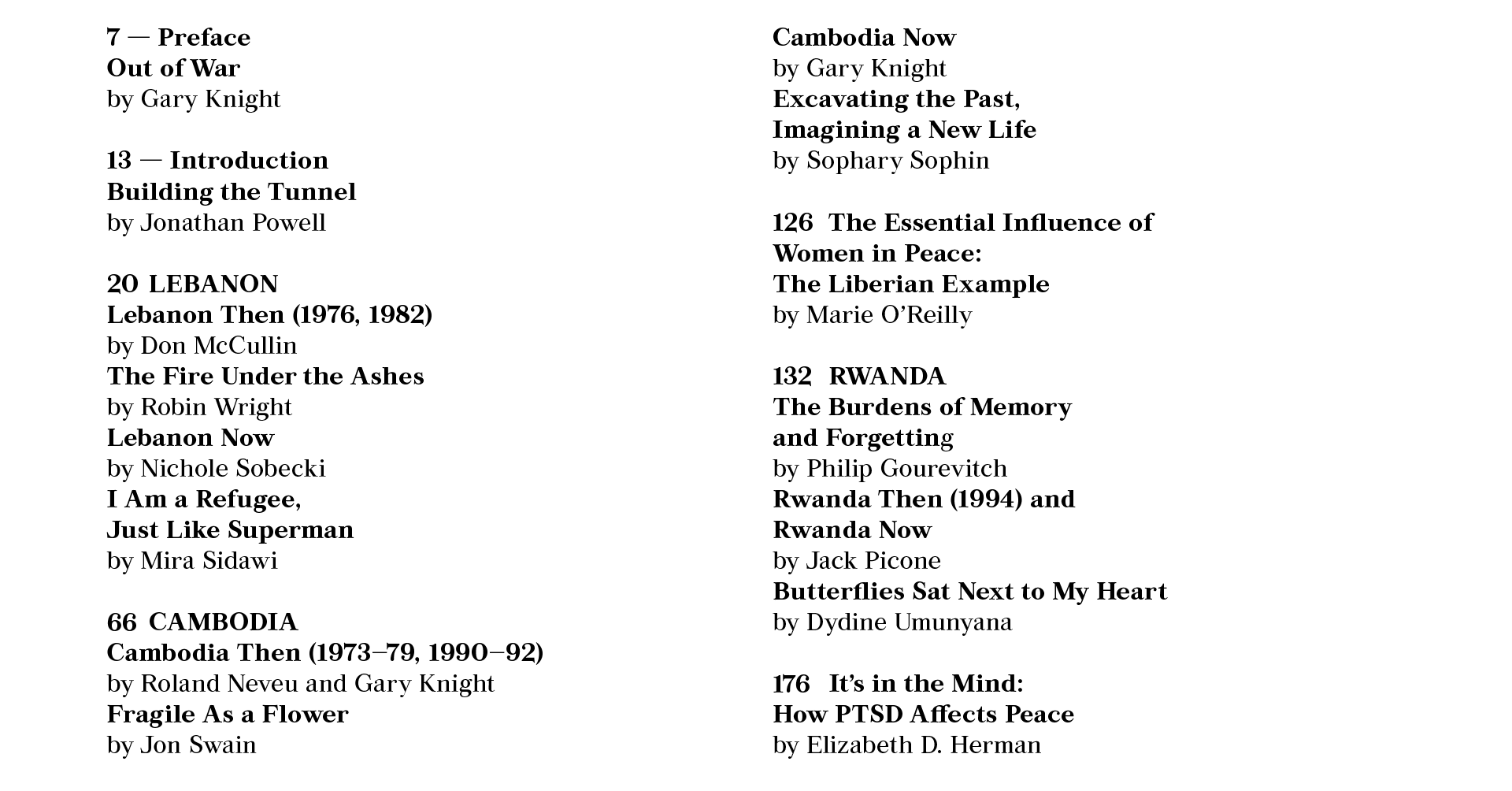

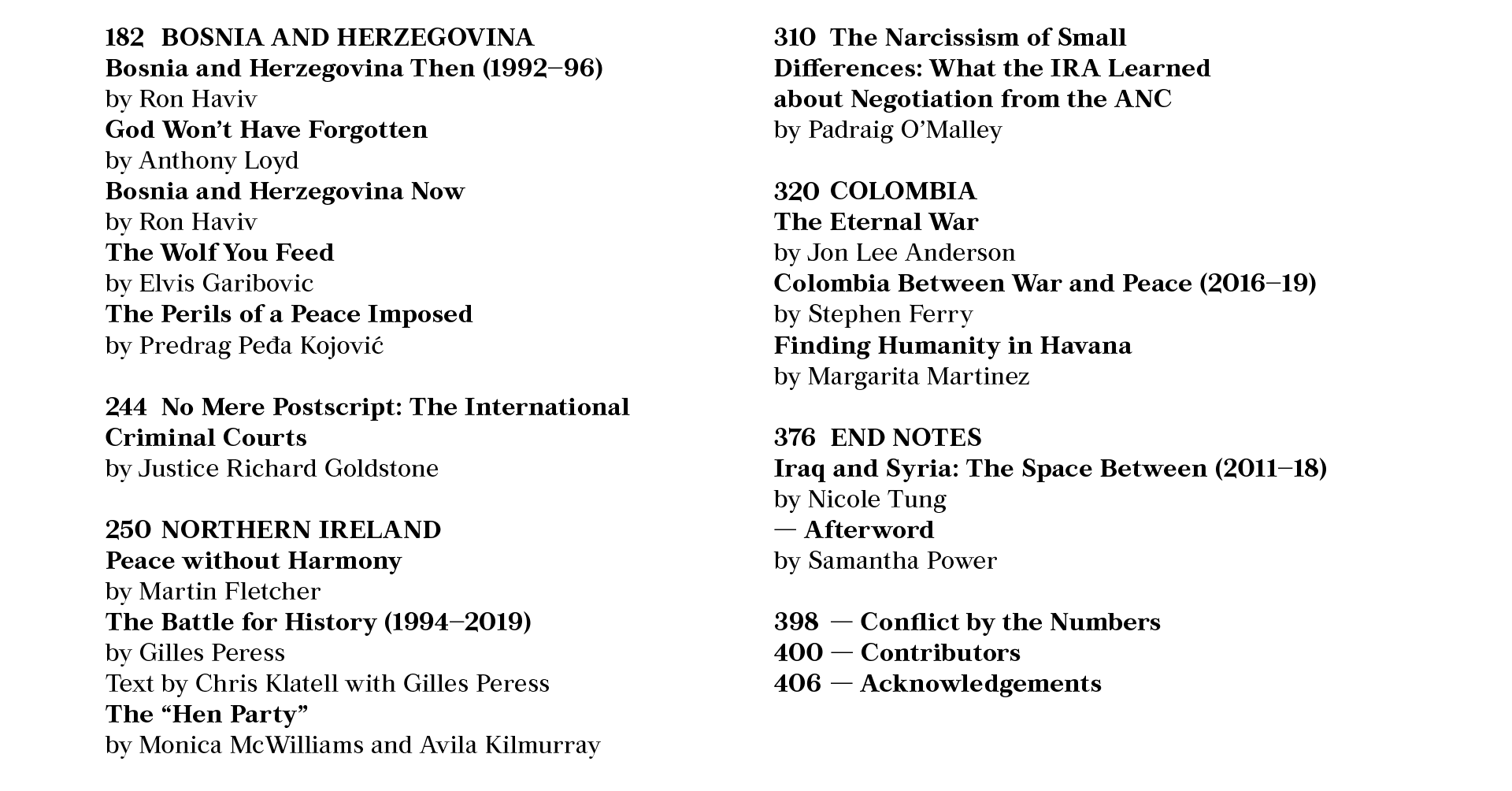

The photographic essays were commissioned from photographers whose lives have been dedicated to covering war and its aftermath. We have essays spanning decades from Gilles Peress in Northern Ireland, and we follow the literal path to peace by Stephen Ferry as he accompanies the FARC out of the Colombian jungle towards a decommissioned future. Don McCullin gives us a visceral view of Beirut in war in the late 1970’s, and Nichole Sobecki takes us to its streets today. In Rwanda Jack Picone returns 25 years after the genocide and is surprised at the order and advancements the country has made. Ron Haviv documented the war in Bosnia and returned to find the changes, a generation later, much fewer than expected. In Cambodia, Roland Neveu was photographing when the Khmer Rouge took over Phnom Penh; 45 years later, Gary Knight photographs individuals who still live in the wake of war. Finally, through Nicole Tung’s lens, we get glimpses of the fragile yet emerging peace that can be found in Mosul and Raaqa.

Over twenty testimonials explore the experience of post-conflict life which happens at both the national and the deeply personal level. In Beirut, veteran reporter Robin Wright sees the clash between past inertia, often reflected in the older generation, and progress and unity, embraced by a younger generation starting new restaurants and experimenting with new forms of leisure. Meanwhile, Mira Sidawi, a Palestinian artist living within a refugee camp, sweeps us along in her dreams of freedom. We see from Philip Gourevitch’s reporting how the nation of Rwanda has made surprising advances. Yet for Rwandan survivor Dydine Umanyana, three years old at the time of the genocide, peace didn’t come until after years of enduring the trauma of domestic violence. We rarely hear about such postscripts to conflict, but Elizabeth D. Herman offers her own research on the PTSD that surfaces in the wake of war.

Peace processes are rarely straightforward. Jonathan Powell, former chief of staff to UK Prime Minister Tony Blair, and chief negotiator for the Good Friday negotiations in Northern Ireland, describes how both sides need to take risks in breaching the divide between governments and combatants. “Shared risks can foster a bond”, he says of secretive and risky meetings with the IRA, early on. Padraig O’Malley, academic and peacemaker, doubles down on the need for bravery amongst adversaries with his role of middleman in bringing together a remarkable meeting between the ANC, Sinn Fein and the Northern Irish political parties that eventually helped pave the way to an IRA ceasefire and the opening of the peace talks. That the efforts paid off was also a credit to the determined presence of bipartisan women present at the talks. Monica McWilliams and Avila Kilmurray recount the part played by the Northern Ireland Women’s Coalition, which brought focus to civic issues that were otherwise ignored by the major parties. The role of women is further explored by academic researcher Marie O’Reilly, in “The Essential Presence of Women in Peace.”

It is possible to identify some preconditions for successful peace. The documentary filmmaker Margarita Martinez watched the peace talks in Havana, where the government of Colombia and FARC guerrillas faced off. They broke through their terse standoff only after witnessing the searing testimony of victims and settling on a formula for restorative justice. Others add to Martinez’s portrait. South Africa’s truth and reconciliation commissions, and Rwanda’s gacaca tribunals were keys to peace in those countries. Justice Richard Goldstone writes about the role of the International Criminal Courts in a world where there are few clear “victors” to set the terms, and where simple amnesties for both sides may be impossible. Anthony Loyd eloquently writes about how forgiveness allows some in Bosnia and Herzegovina to move forward, and Elvis Garibovic writes from his own experience of ethnic cleansing and how he came to terms and moved on.

Politics and politicians—and the governments they create—are essential to allowing peace to take flower—or founder. Predrag Peđa Kojović tells a cautionary tale of a constitution imposed on a populace in Bosnia and Herzegovina and the dysfunctional system that resulted. Jon Lee Anderson, reporting on Colombia, shows how one leader can invest in peace, only to have democratic processes threaten that effort. And Jon Swain, who was present when Cambodia fell to the Khmer Rouge, finds a corrupt government in place today. A peaceful society is not necessarily a just society, or even a thriving one.

Finally, in a forward-looking afterword, Samantha Power makes the case for the book, arguing that we have a responsibility to scrutinize efforts to establish peace with the rigor we bring to analyzing the causes and consequences of conflict. Above all, we must increase efforts in diplomacy and conflict resolution at an early stage.